|

GOING

BACK TO PLACES THAT I

HAVE NEVER BEEN

Being

a Field Guide to Hanoi and Dien Bien Phu for

Historians,

Wargamers and the More Discerning Type of Tourist

by

Peter

Hunt

Postface as Preface

Two decades after this first article was

written, Peter was awarded his PhD from King's College London for his

research on Dien Bien Phu. You can find the details here: https://www.dtfdtw.org

This site includes an updated, (as of 2019,) and

more detailed battlefield guide.

Part

One: Hanoi

To

Start at the Beginning

I was born in 1956 and, have been to

Hanoi and Dien Bien Phu hundreds of times since I was a teenager.

But I haven’t been there since 1954 and, until a few months ago,

had never actually set foot in either place.

From this paradox you will realise that I am the archetypal

“armchair traveller”. Even

worse, my love of history and wargaming makes me an “armchair

strategist” as well. Fortunately,

I’m not a complete couch potato. I

really do like to travel, and it’s not a real holiday unless I can combine

the trip with some serious history or, joy of joys, a battlefield to walk.

This being the case, its always been rather odd that, despite having

spent a quarter century in Asia , I had never visited the battlefield that interests me

the most:

I

suppose I had good reasons for not making the trip.

In 1979, we had the Sino-Vietnamese War.

Then came the refugee boat people from Vietnam

to

Hong Kong. After them

came the economic migrants and the riots in the Detention Centres of the

late 1980s and early 1990s. When

all this settled down it was clear that my wife didn’t trust me alone with

40 million Vietnamese women. Eventually

however all these obstacles receded and I boarded the early flight for Hanoi

one Saturday morning in August 2002.

By way of a little health warning, I must stress that my aim in this

piece is to highlight the bits of my trip that will be of most interest to

the wargamer and history buff obsessed with the war in French Indochina like

me. There is a lot more to Vietnam

than this. I

love the place and the people, but this article is going to be long enough

anyway without going into detail on the country, or culture or even the

“Second Indochina War”. So

if you are still with me, lets take a trip to a place a thousand miles away

and fifty years ago.

Before

You Go

If you are going to get the most out of this trip then you have to do

your homework. You will devour

everything by Langlais, Bigeard, Bernard Fall, Howard Simpson, Jules Roy,

Lucien Bodard, the films of Pierre Schoendoerffer and the accounts of

everyone else who was there and commit them to memory: there will be a short

test later. For the more mundane

travelling aspects you will need the “Lonely Planet Guide”, (but ignore

it’s very dodgy history bits). For

the good of your own conscience you also have to read Greene’s “The

Quiet American” and Bao Ninh’s “The Sorrow of War”.

I’ll explain why later.

Vietnam

is not an expensive place but it can be very hot, wet

and sweaty. Therefore it’s

wise to reconsider the usual formula of taking twice as much money and half

as many clothes as you think you will need for the trip.

If you want to be comfortable, you will need at least two or three

changes of clothes a day. Having

said that a shirt and a pair of slacks costs all of HK$5 (sixty cents US) to

get laundered in Dien Bien Phu so the logistics are quite simple.

While we are discussing money “Lonely Planet” recommends taking

small denomination US dollars. However,

I found that the Vietnamese Dong and the US Dollar are parallel currencies,

freely interchangeable at 15,000 to one.

So you don’t have to worry about getting lots of small US bills before you go.

However, carrying millions of Dong around with you does take up

pocket space so take your stash in high value US and change them for Dong as

you need them.

First

Impressions of

Hanoi

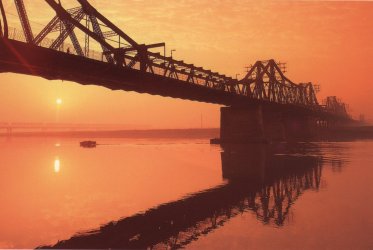

Long

Bien

Bridge

(photo: Hoang The Nhiem and

COVIT)

The Dakotas no longer fly in to Bach Mai or Gia Lam, but as you drive

in from the new airport you will see that the Red River is just as red,

(well pink,) as it always was. The

Paul Doumer Bridge, designed by Monsieur Eiffel is still there too.

Now it’s called the Long Bien

Bridge. A really

good account of an American attempt to take it down is contained in Ethell

and Price’s “One Day in a Long War”.

My favourite story about the Bridge is that, because during the

second Indochina War most of the traffic was from the north, the southbound

side of the bridge started to subside. To

correct the list the Vietnamese reversed all the approach roads so that the

southbound traffic travelled on the northbound lane.

You have to admire a people who can come up with such a simple, but

clever solution to a problem. Before

you get too romantic about the Bridge, Hanoi and even the war itself, (its

not difficult,) consider that it was from the Bridge that the French

counterintelligence “Detachements Operationels de Protection” used to

dispose of the bodies of their victims.

Of course the Viet Minh were just as bad.

It was truly a “dirty war”.

It is about half an hour’s drive from the new airport to the

Bridge. In that short time, two

things will have made an impression on you.

Firstly the traffic, or more precisely the motorbikes.

Thousands of them. They

move like shoals of reef fish: whilst

the mass moves roughly in the same direction, the individuals bob and weave

around each other in the most chaotic fashion.

The average occupancy rate of the bikes seems to be about 2.4

persons: three up is common, and four not unusual.

About one in a hundred riders wears a helmet and this contributes to

the attrition rate because sadly they don’t always bob and weave enough.

There are a thousand fatal traffic accidents a month in Vietnam, (by comparison,

Hong Kong, with one-eleventh of the population, has 14.)

I don’t want to be flippant but its clear that the Japanese are

running up a far higher body count with Hondas and Suzukis than the

Americans ever did with B52s. However

the Vietnamese motorcyclists do not totally eschew protective equipment.

Because of the dust, most of them wear facemasks.

Not the boring white surgical masks that you see in China

but gaily coloured scarves worn folded to a triangle to

cover the nose and the bottom half of the face, just like the bad guys did

in the Wild West. You cannot

escape the feeling that at least one of these characters must be the Lone

Ranger. Just when you thought

that was bizarre enough, you notice that a lot of the ladies wear long silk,

ball gloves that reach their elbows so that their arms don’t get

sunburned. The result is

ridiculously elegant.

The other impression that struck me is that about one in every five

shops is a cafe. Not necessarily

anything grand, maybe just a shack, but still an indication that the

Vietnamese are a cafe society. They

like to congregate and they like to take the time for a bowl of soup, or a

cup of coffee from the Central Highlands that will take at least five

minutes to filter properly through its tin sieve.

The centre of Hanoi

is even more cultured, some streets seem to be composed

of 50% art galleries and 50% ice cream parlours, a combination that is hard

to fault.

Where

to Stay?

“Lonely Planet” will give you options for every budget, but for

the buff there is only one real choice: the Metropole.

The Metropole was already old when the Indochina War was new.

It was the best place in

Hanoi

then, and is the best place now.

Today it is full of international businessmen and well heeled

tourists but its not hard to imagine it when it was full of Mobile Group

Commanders fresh from the paddies of the delta and rugged paras fresh from

the highlands, all revelling in the first decent bath and clean uniform for

weeks. In the bar they have a

Graheme Greene Cocktail, which they wouldn’t have had in 1954 but it’s

not bad for all that. Sadly they

have no idea how to make a “Kepi Blanc” but then neither do I.

Everyone in Schoendoerffer’s film drinks them and I’d love to try

one. If anyone has the recipe

the barman would be pleased to make one for you.

When I was a student I had the album cover from Joan Baez’s

“Where are you now my son?” on my wall.

Bits of that record were taped in the Metropole during the Christmas

Bombing of 1972. Now you can get

a B52 cocktail in the bar, (and, in fairness, in every other bar and

restaurant in Hanoi.) I wondered

what Joan would think? I

certainly found it a little strange. But

then again I found nothing odd in ordering a Pernod with ice (“with lots

of ice,” stresses the character in “317th Platoon”), to

wash away the dust of a delta I have never been to.

Even if you are not staying at the Metropole drop in and look at the

staircase in the lobby. It was

here that Langlais, who had broken his ankle parachuting into Dien Bien Phu

and was convalescing in the Metropole, bumped into de

Castries who had just been given command of the camp.

De Castries wanted Langlais to command the paratroopers at Dien Bien Phu

but Langlais said he wouldn’t be able to march

normally for a month. “Bah!”

Replied de Castries, “I’ll find you a horse.” Langlais took the job,

flew back to Dien Bien Phu

and found a horse waiting for him.

A few days later Langlais, still mounted on his charger, led his

paras on a 20 km march to try and save some of the pro-French Tai guerrilla

companies that were retreating towards the camp.

The path was too rough even for a mountain pony so Langlais had to

make most of the march on his broken ankle, giving, as Fall puts it “his

first

lesson in leadership to his new command.”

Getting

Around

You have four options, all of which are interesting.

Firstly, there are plenty of air-conditioned taxis.

They are clean, safe, run on the meter, (which is more than you can

say for many South-East Asian countries), and the flag fall is only Dong

11,000.

If you don’t mind taking your life in your own hands there are

motorbike taxis. Most of these

are professionals, i.e. men who sit or drive around looking for business,

but I also got the impression that there are many enthusiastic amateurs who

are just cruising around and, if you are happy to pay for their petrol then

they are happy to cruise in any direction you want to go.

There is a certain etiquette to being a motorbike taxi passenger.

Apparently it is not the done thing to hang on for dear life to the

driver and shout blandishments in his ear about avoiding the other

motorbikes and paying particular attention to the colour of traffic lights.

Instead you are expected to lounge on the back, hands free, in the

most casual way. It is also

considered good mannered to strike up a conversation with the passengers on

the bike next to you, ignoring the fact that you are doing 70 kph and that

they are only a foot away. Thus

motorbike trips demand a certain sangfroid.

Personally, I feel very nervous in any vehicle that does not have

four wheels on the road and one in my hands so I did not take too many bike

trips. Being drunk helps a lot

though.

The pedal rickshaws or cyclos are much more fun.

They tout in the most refined manner:

“Cyclo Sir?” And if

you decline that they come back with: “Lady?”

As if they had Catherine Deneuve tucked away around the corner just

for you. If you do want to go

somewhere you say where and they quote a price of one US Dollar.

You politely point out that you could get an air-conditioned taxi for

that price, they drop the price accordingly and off you go.

You then have a marvellous time pretending to be Donald Pleasance,

pretending to be Howard Simpson in “Dien Bien Phu”, uttering things like

“Mau Len Old Crab” which the driver completely ignores.

When you arrive at your destination you give him the dollar he wanted

in the first place and you are both happy bears.

Finally you can walk. Despite

the heat Hanoi is a good walking city.

It is dead flat. There

seems to be a bar, cafe or ice cream parlour every five meters so you never

lack for sustenance. All the

shops and galleries are interesting and everything is relatively convenient

if you are based at the Metropole or near Hoan

Kiem Lake. When it

comes to crossing the roads about 80% of the motorbikes stop for red lights

so you have a sporting chance. There

are a few beggars (who actually look like deserving cases,) hawkers and

moneychangers, but none are persistent or troublesome.

The most interesting are the younger hawkers who hang around the

tourist spots all offering exactly the same things, which they invariably

trot out in this order: Postcards?

“No thanks.” Phrase

Book? “khong,” (“No thanks” in Vietnamese, witty what?) Quiet

American? “Read it.”

Sorrow of War? “Read that too,” (so now you get my point about

those books.) Marijuana? “No

thanks.” Girl?

“No thanks.” Boy?

“No thanks.” Once you have

got through this list they give up, no doubt amazed at your self-control.

After one or two encounters you can just cut to the chase.

The purpose of all this travelling is to get to the history of the

place. Beware; all the museums

are closed on Mondays and some, on Saturday afternoons, Sundays and Tuesdays

too. (You guessed it, my stay

included a weekend!) They also

tend to have a Siesta, usually between

11:30 a.m.

and 2 p.m.

Admission

usually costs Dong 5,000 or 10,000 and there is an additional charge for

photographs of between Dong 2,000 and 5,000.

Most artefacts in all the museums tend to be well described in

Vietnamese, English and French so you will have no problem knowing what you

are looking at, although you may have trouble seeing it because the lighting

is usually very gloomy. Take a

powerful flash for indoor photos, I didn’t and lost about half of my

museum shots.

The

Military

Museum

Like

me, you will probably make a beeline for the Military

Museum

on the appropriately named Dien

Bien Phu Street. The taxi from

the Metropole is only Dong 15,000.

Outside they have one of the T55s that took out the gates of the

Presidential Palace in Saigon

in 1975. They

have another tank from the same squadron inside.

Modellers might like to note the length of the radio aerials.

I always think that aerials bring a wargames vehicle to life but the

difficulty is getting them to look right, and half of that problem is the

length. The aerials on these

vehicles must be 4 or 5 meters long so don’t be too conservative when you

come to detailing your kits. There

is also an American 105 mm howitzer outside which, according to the plaque,

was captured by the Viet Minh at Nghia Lo in 1952 and used against its

previous owners at Dien Bien Phu

two

years later. Much is made of the

material support given to the Vietnamese by the Chinese,

but this gun is a good example that the Viet Minh acquired a fair proportion

of their kit the hard way.

|

|

|

|

Military

Museum – one of the Saigon T55s |

Military Museum – the Nghia Lo 105

mm |

On the ground floor of the main building there is a gallery dedicated

to the “combat mothers.” In

the First Indochina War these were the women of the local community who

provided the cooks and nurses to support the first line and regional forces

and thus alleviated these units of the need to maintain an administrative

“tail.” A good first hand

description of their work is in Dang Van Viet’s “Highway 4”, and Greg

Lockhart in “Nation in Arms” also stresses their importance.

During the Second Indochina War the description was expanded to

include mothers who had lost three family members for the cause.

Although there is not a tank or gun in sight this gallery, more than

any other in the Museum, exemplifies the true human cost of the 30 years of

struggle in Vietnam.

The First Indochina War is well covered on the entire first floor of

the main building. The galleries

are laid out in chronological order from 1943 to 1954.

The origins of the PAVN, the founding of the Democratic Republic and

the march to the South are well covered, as is the battle for

Hanoi. The events

of 1949 to 1953 tend to be lumped together and then the last room is devoted

to

Dien Bien Phu. As well as

the artefacts and some dioramas each theme is also well illustrated with

albums of photographs that are truly fascinating.

If only these photographs were available for sale!

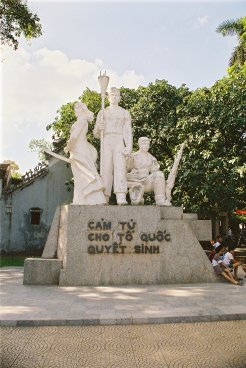

Battle

of Hanoi Monument near the lake.

Note the “Panzerfaust on a stick"

There are two particular weapons in the early rooms that caught my

imagination. The first is in the

display of the Battle of Hanoi in December 1946 and can best be described as

a “panzerfaust on a stick”. The

English translation calls it an “anti-tank bomb” and it consists of a

hollow charge cone with three detonator pins protruding from it, stuck on

the end of a five foot pole. There

are photographs of Viet Minh carrying these weapons (but not using them,)

both in this museum and in the one at

Dien Bien Phu, (the one at the latter is titled “Commandoes Du

Mort” in French, and more prosaically “Suicide Squads” in English.)

The statue commemorating the battle at the northwest corner of

Hoan Kiem Lake

also shows one. The

version in the diorama at the museum has a thick bronze cone.

If this is not a sculptured representation, (which I suspect because

it is located next to a bronze statue,) then the explosive must have been

contained in the smaller hollow of the cone.

If this is a sculptured representation then the cone itself was

probably made of thin metal lined with explosive to make the hollow charge

warhead. A third option is that

it is designed to hold an anti-tank grenade such as a Russian RPG-43,

although the Viet Minh would not have had access to Russian grenades in

1946, or the Japanese hollow charge grenade which the Viet Minh certainly

would have had access to. However,

if this was the case two questions arise: why not just throw the grenade

anyway, and why do none of the illustrations show the device with the

grenade fixed? Presumably, the

idea was to run up to the enemy tank, push the warhead against the side

which would depress the firing pins, (which could have been simple metal

rods bearing on pistol cartridges,) and these would set off the hollow

charge explosion. The operator

then hopes against hope that the hollow charge arrangement will concentrate

the force of the explosion to the front, and blow up the tank, not him.

This is all conjecture on my part, and if I’ve got it wrong I’ll

be happy to stand corrected, but it seems the only logical

way that the weapon can have been used.

On reflection the English description at Dien Bien Phu

seems pretty accurate.

The other weapon is described as a “65 mm SKZ gun

〔recoilless

rifle〕

produced by a Southern Arms Workshop in February 1952.”

It looks like a cross between a 57 mm RCL and a Carl Gustav Rocket

Launcher, but, for what is essentially a homemade weapon, it looks like a

quite sophisticated and very effective piece of kit.

The

Dien Bien Phu

room is the largest, and is full of goodies.

As well as the usual collection of weapons and photographs several

items struck me. First, they

have de Castries’ walking stick, (its what the English would call a

“Shooting Stick” because you can fold out the handle to sit on it.)

Then in one corner you will see maps laying out the plan for the

January attack which was all set to go but which Giap cancelled at the last

minute in the face of opposition from his Chinese advisors and his field

commanders. This is described in

his book “The Hardest Decision” and is one of the great “what ifs?”

of the battle. Finally, there is

one of the transport bicycles that were a key part, (albeit alongside a

fleet of Russian trucks,) of the Viet Minh logistics effort for the battle.

Since the French had calculated that the Viet Minh could not supply

more than a couple of divisions in the north west

of Vietnam this factor was decisive.

The key was that an individual porter carrying say 20 – 30 kg of

rice on his back from the Vietbac, north of Hanoi, to

Dien Bien Phu, 200 miles west of Hanoi, he would have to eat most of the rice on the way.

However, give the same porter a bicycle and he could move 200 kg on

average, and the strongest over 300 kg.

A really good account of how they did it is in “The Brigade of Iron

Horses” by Dinh Van Ty in Vietnamese Studies No. 43.

Modellers should note that tyres of the bike are pink, yes pink, and

since the one in the Dien Bien Phu Museum

is the same I think that we can take this as definitive.

It’s not a “fru fru” pink but a sort of dirty, very washed out,

whitish, salmon pink. Britannia

Miniatures do a porter with a bicycle and both Raventhorpe and FAA make 20

mm bikes you can convert, so go to it!

But the main feature of this room is a diorama of the battle, which

is about 10 m x 4 m showing the whole valley.

The course of the battle is depicted through a strident soundtrack

and video shown above the model whilst little red lights and arrows show the

attacks. The 15 minute show

culminates in a little Vietnamese Flag being raised above de Castries’

bunker in the middle of the model. The

video show and narration is presented in Vietnamese, English or French

depending upon the audience. The

video is a bit “iffy”, for instance it shows pictures of French paras

jumping out of Noratlas transports which didn’t arrive in

Indochina

until long after Dien Bien Phu

fell, but it also includes lots of shots from Karman’s

recreation of the battle from the Viet Minh side so it is still worth

watching. The Museum souvenir

shop is right next to the diorama. There

is not much of interest in it but I was able to buy a copy of the video, the

last one they had. It’s the

French version, and I have a sneaking suspicion that it was only available

because they were using the Vietnamese and English versions that day!

If this is the case, I apologise to any future French visitors out

there.

Downstairs in the main building is an art gallery, but this is a

commercial venture and the content is not related to the Army.

There is nothing wrong with this but Hanoi

is full of good art galleries and it would have been

nice to have an exhibition of revolutionary art and propaganda posters.

Sadly, I stumbled into a disused gallery in the second building where

I found a junk pile containing several French anti-war posters from the

1950s that would have made a good exhibit.

The courtyard of the Museum is full of all kinds of ordinance, from

Japanese 70 mm battalion guns to American 155 mm SPGs.

There is also a huge pile of shot down American aircraft wreckage.

On the ground floor of the second building is a gallery devoted to

the Vietnamese Veterans of the wars and the military grave registration and

body recovery organisation. Whilst

the issue of the American MIAs has, quite rightly, attracted a lot of

attention, this exhibit, which covers the search for American MIAs as well,

brings home the enormous task facing the Vietnamese in recovering and

honouring their own dead, which is all the more significant given the

Vietnamese respect for family ancestors and the dead.

Boa Ninh’s “Sorrow of War” gives good insights into this work,

(so now you have two reasons to read the book.)

The rest of the second building is dedicated to the “Second

Indochina War” with heavy emphasis on the 1975 campaign.

There is much of interest and it is well presented.

I particularly liked the recreation of the Ho Chi Minh trail,

complete with a variety of American airdropped sensors.

There are also several examples of bombardment rocket launchers used

by the NVA and Viet Cong. I had

heard the launchers described as “any

old bit of tube” and that is

exactly what these are. Their

simplicity is quite mind-boggling.

The Citadel

Before you leave the Museum, you can walk up to the terrace of the

citadel with the flag tower above, a true landmark of Hanoi whether there

was a Tricolour or the Gold Star of the Democratic Republic flying from it.

It was only after I left the Museum that I realised that, although

there had been a few photographs of the campaign in Cambodia

to topple the horrendous Pol Pot regime, and the

guerrilla war against the Khmer Rouge that followed, there had been no

reference at all to the 1979 Sino-Vietnamese War.

Over a Graheme Greene Martini back at the hotel, I asked the barman

who was kindly translating my notes, about this.

He pointed out that the Chinese Embassy was directly opposite the

Museum so references to the war, let alone any suggestion of a Chinese

defeat, at such close quarters, would be unthinkably impolite.

However, the Vietnamese had no doubt that their cause was right and

this was evidenced by the statue of Lenin that is the centre piece of the

park between the Embassy and the Museum.

Vladimir Illyavitch has his back firmly to the Chinese and gazes down

encouragingly on the Vietnamese army!

The

Air

Force

Museum

Situated on D. Truong Chinh, a Dong 40,000 taxi ride south of the

city centre, the Air Force Museum has a large forecourt full of aircraft and

vehicles and one large exhibition hall.

Although the VPAF was not formed until after the French war, there

are still a few exhibits of interest to the Indo buff.

Anyway I love looking at aeroplanes so I spent a happy couple of

hours pottering around.

For those who must hark back to 1954, there is an M3 halftrack in the

forecourt and a sign that says it was captured from GM 100 in 1954.

I doubt this. Firstly the

vehicle sports ARVN camouflage, (compare and contrast to the M 113 next to

it;) secondly, it does not appear to have any damage, (the tracks are

falling off but that appears to be due to old age, not to SKZ rounds;) and,

finally, how did the Viet Minh get it to Hanoi?

Even if it was taken intact from GM 100, I doubt that it could have

been moved north when the Viet Minh regrouped in 1954-55.

In the Da Nang Museum there is an M8 Greyhound armoured car that is also

alleged to have been taken from GM 100 and I have my doubts about that

vehicle too for the same reasons. I

can’t categorically say that the Museum has it wrong, and I sincerely

apologise if it is me being overly suspicious, but I suspect that this

vehicle was captured from the ARVN or taken from ARVN stocks after 1975.

Anyway, it remains a good example of an M3 so it is worth a look, and

who knows, maybe the ARVN got it from the French and it was part of GM 100?

|

|

|

|

Air Force Museum – a brace of MIG

21s |

Air Force Museum – the suspect half

track |

The rest of the forecourt is chock full of MIG 21s; Freedom Fighters

and Cessnas taken from the South and used against their previous owners and

the Khmer Rouge; helicopters and even an AN 2 biplane transport.

Lots to keep the aero nerds among us happy.

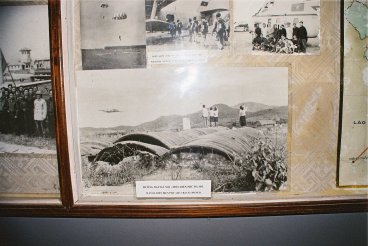

The exhibition hall is one big, badly lit, room that traces the

history of the VPAF. There is an

interesting photograph of the first VPAF flight out of

Dien Bien Phu

that shows the corrugated roof of what must be the

hospital, because it has too many arches to be de Castries’ bunker.

Next to this photo is a pedal generator for a radio of the type that

you see in “The 317th Platoon.”

Other items of interest are a little diorama showing how AN 2

biplanes were used to take out an American radar direction beacon in Laos;

gun packs from MIG 17s; and a sawn off MIG 21 that you can sit in whilst

your mummy snaps a pic of her little Brylcream Boy.

As you would imagine most of the room is given over to the air

defence of the North against the American raids.

There are lots of maps of dogfights and pictures of exuberant pilots

describing how they shot down the bogey with their hands palm out in front

of them at improbably strained angles. The

age, the look in the eye, the wide smiles and the poses of these guys are

exactly the same as you see in any photograph of a fighter pilot from 1915

to today. Take away the

different flight suits, ignore the colour of the hair and skin and these men

could have been in a circus with

Richthofen, some of the “Few” or Phantom jocks off a carrier on Yankee

Station.

|

|

|

|

Air Force Museum –

the DBP Hospital |

Air Force Museum – the Soyuz

|

Being a child of the Space Race myself, astronauts and cosmonauts

have always been my special heroes, so the crowning, and unexpected, joy of

this museum was the Soyuz capsule used to bring back two Vietnamese

cosmonauts from MIR. Proof, not

that it was needed, that the VPAF does have “The Right Stuff.”

The

History

Museum

On Pho Pham Ngu Lao just behind the Opera House and around the corner

from the Metropole, The History Museum is located in a lovely building and

picturesque gardens. There is a

nice little cafe in the grounds so you can take a morning coffee or

afternoon beer to fortify you. The

Museum takes the history of

Vietnam from pre-historic times to 1945.

Thus, although only the last exhibit is of direct interest to the

1945-54 buff the museum is an important insight into the Vietnamese psyche

that stresses national unity and struggle against foreign aggressors

~ which, as this place shows, have usually been Chinese with the

French and Americans being only relatively short term interlopers.

If you are like me, and have only a sketchy idea of Vietnamese

history before French involvement, and base your knowledge of their military

history on DBM Army Lists, then this museum will be a painless education.

The galleries are arranged chronologically so you take a walk up

through time. There are lots of

dioramas, maps and weapons from

Vietnam’s many wars against the Chinese.

The highlight is a set of stakes that the Viets used to trap a Yuan

fleet in the Red River Delta. I

think the point of the whole place is to bring home the idea that unified

national struggle and the ability to conduct the “war of the tiger against

the elephant” has been a Vietnamese characteristic time out of mind.

Before you leave take a careful look at the cabinet that deals with

the French encouraging the opium trade.

On the right hand side, you will see a photo from, I think, about the

1890s, featuring a portly European sitting in a rickshaw.

He is a dead ringer for yours truly.

This won’t bother you but I was left with a really spooky feeling .

. . funny places, museums.

The

Museums I didn’t get to

Of direct relevance to the Indo buff are the

Revolutionary Museum, located on Pho Tong Dan, just North of the

History Museum and east of the Metropole; and the Ho Chi Minh Museum

located next to the great man’s mausoleum.

The Hoa Lo Prison Museum on Pho Hoa Lo concentrates more on the

Vietnamese detained by the French rather than the Americans detained by the

Vietnamese but either way it should be well worth a visit.

Just don’t arrive on a weekend like I did and you can take it in

too.

The

Tourist Bits

Just down from the Metropole is the Hanoi Opera House.

When news of the Japanese collapse reach Ho in 1945 he made a beeline

for Hanoi and, on August

19, announced the end of

French rule, the defeat of the Japanese and the triumph of the proletariat

from the Opera House. It was also here,

on 30 March 1954, that General Cogny the theatre commander in North Vietnam,

was enjoying a concert when he should have been in his office

arranging

reinforcements for Dien Bien Phu as the Viet Minh

launched their second major offensive ~ the Battle of the Five Hills.

The initial Viet attacks drove the French of the key hills of D2 and

E1. Both hills were recaptured

the next day but couldn’t be held for lack of troops.

The importance of D2 comes home to you when you see it “in the

flesh” and realise how it dominates the whole position.

The Viet Minh had suffered badly in the attack and counter-attack so,

if French reinforcements were available, the hills might have held ~ a case

of a “stitch in time saving nine”. The

reinforcements were available in Hanoi and could have done the job if Cogny had given the order

instead of spending a night at the Opera.

During and after the war, there was an acrimonious dispute between

Cogny and Navarre, the Commander in chief for all of

Vietnam, about who was to “blame” for the loss of

Dien Bien Phu. My personal

take on this is that Navarre put

Dien Bien Phu

in a position where it could be lost, but by not doing

his job on that spring night, Cogny almost made certain that it would be

lost.

|

|

|

The Opera

House |

Anyway, the Opera House is a lovely building, beautifully restored

inside and out. Try and take in

one of the Sunday concerts. $10

US will get you the best seats in the house and during the interval drinks

are taken in the garden. Its all

very nice, very splendid and very evocative of a war that was over before I

was born.

The other cultural must do is a visit to the Water Puppet Theatre at

the top end of Hoan Kiem

Lake. Although

not as high brow as the Opera House, it will appeal a bit more to your inner

child. Go first class and they

give you a tape of the music that you can use to accompany your wargames

when you get home.

If you are looking for a spot of supper after the puppets, or

somewhere to spend a languid afternoon, the Thny Ta Cafe at the Northwest

corner of the

Lake

would be my choice.

It features in Schoendoerffer’s movie as the terrace by the lake

where the Simpson character and the Schoendoerffer character watch the

“banjos” of Dakotas

heading off for

Dien Bien Phu.

“Schoendoerffer”

is annoyed because he has to cover Cogny’s concert and can’t fly to

Dien Bien Phu

until the next day.

Nowadays, Vietnamese courting couples go there for the ice cream

sundaes and westerners go there for the pizza.

My vote was for a plate of Vietnamese spring rolls and a bottle of

French wine.

There were no

Dakotas

but I didn’t mind too much . . . because next day I was

flying to Dien Bien Phu.

back to

vietnam

go

to part two

|