|

GOING

BACK TO PLACES THAT I

HAVE NEVER BEEN

Being

a Field Guide to Hanoi and Dien Bien Phu for

Historians,

Wargamers and the More Discerning Type of Tourist

by

Peter

Hunt

Part

Three: West of the River and

Beyond

The

Bailey bridge across the

Nam

Yum

River

is still in daily use.

So in this respect the battle is at least doing some good for the

people of

Dien Bien Phu

even 50 years later.

The Bridge itself was a later addition to the infrastructure of the

French position. The original

crossing over the river was by a wooden bridge further south, of which I

could find no trace. North of

the bridge the river meanders to the new road bridge.

On the eastern side of the river at this point was the “dead arm”

of the Nam Yum where a meander had been cut off.

This is now just an area of boggy ground.

From the Bailey bridge or the road bridge you can get good views of

the “cliffs of the Nam Yum” where the “rats” ~ the hundreds, perhaps

thousands of internal deserters of the camp, lived in dug outs and caves.

The “cliffs” are no such thing, they are really just the steep

banks of the river cut by its meanders into the soft alluvial soil about

three to six metres high.

The Bailey

Bridge and Quad.50

On

the western side of the bridge are two things to note.

On the southern side is a marker commemorating the first Viet Minh

unit to get across. Translated

it says:-

“At

2 p.m.

on

7th May 1954

Company 360, Division 312 attacked and took

Muong

Thanh

Bridge

, striking at the heart of the enemy and inflicting

defeat on the high command of the

Dien Bien Phu

group of fortresses.”

The

jubilation that those men must have felt after the months of siege can only

be imagined. On the north side

is one of the reasons that the Viet Minh took so long to get there: the

remnants of a quad .50 calibre machine gun. There were four of these weapons

at Dien Bien Phu, two placed further north of the bridge on

“Sparrowhawk” and two placed further south on “Juno”, so how this

one got to the end of the bridge is anyone’s guess.

It was probably moved after the battle but it might have been moved

in the last few days of combat. The

quad 50s kept firing up to the last day.

There was no shortage of ammunition, even for their prodigious

appetites, and, unlike the tube artillery they had no recoil hydraulics

vulnerable to near misses from Viet Minh shellfire.

|

|

Quad.50 at

the Hanoi Army Museum |

If

you want to scratch-build a quad 50 Raventhorpe make the upper body as a

conversion for half-tracks. The

lower body is easy to knock up with a couple of aircraft wheels.

Cut up electrical wire provides you with the heaps of brass cartridge

cases strewn around that were the hallmarks of these weapons in action.

Claudine

At

the western end of bridge there is now a row of soup and coffee shacks.

At the crossroads beyond them is where the hospital was.

By the end of the battle this had been extended all the way to De

Castries bunker. To understand

the horrors and heroism that went on beneath your feet, (for the hospital

was mostly underground,) Major Grauwin’s “Doctor at

Dien Bien Phu

” is a must read. Nothing

now remains of the hospital except that old photograph in the

Air

Force

Museum

in

Hanoi

.

At

the road junction a “Bison” Chaffee tank and pile of aircraft wreckage

stand mute testimony to the French defeat.

Turn left and you come to that defeats most memorable visible symbol

~ De Castries’ Command bunker, immortalised forever by the image of that

Viet Minh soldier waving the gold star and red flag of the new

Vietnam

above it.

A

small entrance fee gets you into the bunker, which has been preserved with

concrete sand bags, but the layout, the corrugated steel roof and the

pierced steel plates inside, that were originally used on the French

airstrip, are authentic. The

place is cool even on the hottest days but the gloom and the knowledge of

what went on down there leaves you in little mood to tarry.

There has been no attempt to turn it into a museum of the battle and

the fact that the rooms are mostly empty just adds to the sense of history ~

with nothing there it is easier to imagine the hubbub of the radio traffic,

the desperate messages going in and out; and the anguished decisions being

made. It really is an eerie

place.

|

|

|

De Castries' Bunker |

Walk

back to the road and continue south. Another

“Bison” looks out over the flood plain of the Nam Yum towards Elaine on

the other side. The original

wooden bridge would have been about here but the river and cultivation have

changed things since 1954. This

is a good lookout as it is difficult to get to the river at other points on

this side. You can take in the

length of the central position from the Bailey Bridge to the north, to where

“Juno” would have been to the south.

|

|

The French

Memorial |

Keep

walking south and you come to the French Memorial.

This is an odd little place as it is a “free enterprise” effort

created by an “Ancien” of the Foreign Legion, not an official memorial

by the French or Vietnamese governments.

Still it’s a touching place and all the more so as a “grass

roots” memorial from and to the guys who fought at Dien Bien Phu.

When I visited it was a little bit scruffy and needed some paintwork.

I hope that it is spruced up for the 50th Anniversary.

It deserves it.

Back

at De Castries' bunker you are in the centre of the Claudine positions and

the gun lines are marked by rusting artillery pieces.

Across the road to the north of the bunker there is a 105 mm howitzer

and to the west of the bunker are a 155 mm howitzer and two more 105s.

Further west the Claudine and Francois defensive positions have

disappeared under housing and agriculture so there is not much to see here.

From the layout of the housing you can work out the original path of

the “Piste Pavie” track which was the main north-south route at the time

of the battle but which has now been replaced by the main highway on the

eastern side of the river and the smaller road on the western side.

If you follow this north you will come to the valley’s main

east-west road and yet another Bison, sitting on its own in a little bog.

The Huguettes

Using

this tank as a landmark take the sidetrack to the north and you will be

entering the area of the Huguettes positions which were intended to defend

the airstrip. The first landmark

is the steep sided creek that flows roughly east to west into the Nam Yum.

At the time of the battle this was bridged at several locations

including a special bridge between the airstrip and the dispersal area for

the Bearcat fighter bombers and Morane “Criquets” based at

Dien Bien Phu

. On my visit

all I could find was a narrow footbridge through a farm yard.

Since

the airstrip itself has been moved, extended and concreted I wasn’t

expecting to find much to justify sinking up to my calves in the paddy

fields but I was pleasantly surprised. Huguette

2 is marked by a marker and the last of the Bisons.

The path of the “Piste Pavie” is quite clear leading off to the

site of “Ann Marie”, later renamed Huguette 6 and 7.

Likewise the path of the drainage ditch that used to run on the east

side of the airstrip is still clear, although today it is on the west of the

new strip.

|

|

The

Disconsolate Bison |

The

Bison at Huguette 2 seems the most disconsolate of all the tanks at

Dien Bien Phu

. Its gun

dips sadly over its shattered body. Although

there is nothing left of the trench works the sharp contrast between the

situation on the Huguettes and the “Five Hills” east of the river is

brought home to you. At least on

the hills there was dead ground to take cover in.

Here by the airstrip everything is completely flat.

The soldiers on both sides could only survive because of their

trenches and both sides paid a high cost in blood to extend their own

trenches or take out the enemy’s. One

of the best Viet Minh accounts of the battle is by battalion commander

Nguyen Quoc Tri in “Operation on the Stomach” (Vietnamese Studies No. 3,

March 1965.) It was Nguyen’s

battalion that was charged with digging an approach trench right up to the

airstrip a few hundred meters north of Huguette 2.

The 140 meter trench cost him two thirds of his unit in three nights

and two days of fighting in early April 1954.

I

wasn’t able to walk up the Piste Pavie to the Anne Marie positions because

I was shooed away from the runway by guards as the afternoon plane was

arriving. My advice then is to

visit the Huguettes and Anne Marie in the morning.

Unless you are visiting in dry season a good pair of boots is

essential for these positions which consist mostly of paddy.

The berms between the fields are narrow and the mud is glutinous.

I went in to my ankles of my jungle boots several times, shoes or

trainers would have probably been sucked off.

The walk to Anne Marie would be the longest bit of exploration that

you can conveniently do on foot. To

visit the other positions, Giap’s HQ, Beatrice, Gabrielle and Isabelle,

you need some kind of transport, either a car or motorbike, both of which

you can hire for a day and take in the lot.

Giap’s HQ

Although

it is only 14 km from the centre of

Dien Bien Phu

as the crow flies, the journey to Giap’s HQ in the

mountains to the east takes well over an hour.

But the time is well worth it. Both

the journey and the arrival are an education.

The first half of the route is via Highway 279, the old RC 41 which

follows the river valley of the Nam Yum as it carves its way through the

mountains. As the road clings to

the side of several gorges you get amazing views and an introduction to the

ethnic and agricultural background to the area.

The valley bottoms and lower sides of the valleys are populated and

farmed by the Black Tai whilst the tops of the mountains above you are the

home of the Hmong. The Hmong

fields seem to cling to the very precipices in an almost perpendicular,

gravity defying, way. Leaving

the main road at Na Nhan you head south for the Pa Khoang Lake which

wasn’t there at the time of the battle ~ it is the result of a

hydro-electric project. Just

before you get to the

Lake

you turn east again on a road not marked on the

1:250,000 series

Dien Bien Phu

map and travel through Tai villages to Muong Phang.

Here you leave the car and take a 25 minute walk on a well maintained

path through the forested hills to the great man’s HQ.

The

walk through the woods and over little brooks brings you to a fork in the

path and a signboard telling you that you have arrived.

Take the left fork and you will come to Giap’s hut and the entrance

to the underground bunker system. Take

the right fork and you will come to the hut of Giap’s chief of staff,

Hoang Van Thai and another entrance to the tunnel system.

Just before you get to Hoang’s hut the large briefing hut has been

recreated. This is the building

that usually features in the photographs of Giap planning his battle.

Beyond it is an open space where the Headquarters guard post used to

stand.

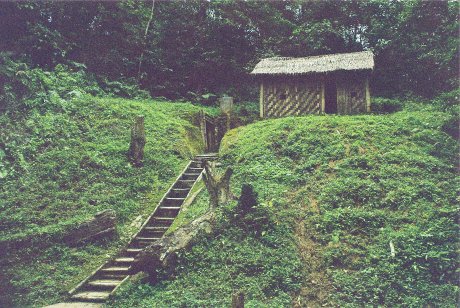

Giap

gives a nice description of how his CP was located and operated in

“Reminiscing about

Dien Bien Phu

(Vietnamese Studies No. 3, March 1965.)

He calls his hut a “shed” which is pretty apt, as it really is no

bigger than a garden tool shed, and waxes lyrical about the location ~ for

which I don’t blame him because it really is an Arcadian setting:-

“Situated

on the side of very beautiful hill …

covered

with tall, slender, chestnut trees …

The

huts roofed with tiger grass were scattered along a small stream.”

|

|

Giap's Shed |

Reading

between the lines of his reminisces also tells you a

thing or two. For instance the

construction of the tunnel complex was not begun until late March.

Presumably after the losses taken in capturing Beatrice and Gabrielle

had convinced the Viet Minh that the battle would take much longer than they

had previously thought. Likewise

if April was bad for the French it was desperate for the Viet Minh too.

Their morale was cracking because of the heavy losses and their

supply was a nightmare. Giap

admits to feeling the strain and some considerate staff officer whistled up

an Army Folk Dance Ensemble to cheer him up.

After banging off the usual patriotic, morale raising tub thumpers

the band started singing traditional country folk songs that seem to have

got to Giap:

“Never

before had I felt the beauty of music as I did then during those tense

moments fraught with a great sense of urgency, close to the battlefield.”

Most

of all Giap stresses how

Dien Bien Phu

was a battle of supply ~ the chart next to his desk

recorded supply deliveries, not friendly and enemy casualties.

I

really enjoyed visiting Giap’s HQ, the journey, the location and the

context were all thought inspiring and very different to the rest of

Dien Bien Phu

. For you

dear reader though, a few words of advice: TAKE A TORCH! I didn’t,

(although I had a perfectly good one back at the hotel,) and thus although

the 300 meters of bunkers through the hill between the two entrances seem

quite open I couldn’t explore them in the pitch darkness.

I hope that you will have more luck and will not have to retrace your

route through the forest saying “Doh!” at every step like I did!

Beatrice

You

can drive to Beatrice, or Him Lam as the Vietnamese call it, on the way to

or from Giap’s HQ or even walk there from the Muong Tranh Hotel.

Head east along Route 279 and stay on the same side of the road as

the hotel. About 300 meters from

the hotel you come to a garage “SUA CHO AUTO”, take a left here down an

unpaved lane. About 800 m down

the track you come to a walled enclosure marked “NHA MAY CACN DBP’.

There are ponds on your left and the track makes a 90 degree right

hand turn around the enclosure, follow the road and after about 100 m it

makes another 90 degree left hand turn.

On this bend is a white house. Don’t

follow the road but from the bend you will see a path leading off to your

right: follow this, it leads up a wooded hill and when you get to the top

you are at the Beatrice monument. I

did this at the gallop because I was overtaken by a section of PAVN

NCO/officer candidates doing a map reading exercise and I didn’t want them

to think that steely eyed oriental crime fighters were fat and flabby.

Keeping up their pace almost killed me but I was not the last

casualty of

Dien Bien Phu

and finally got to the top without a heart attack.

They politely but firmly decline my offer of a photo.

The bush is about waist to shoulder high on top of Beatrice. I

briefly turned away from the soldiers to photograph the monument and when I

turned back they had totally vanished. This

was rather spooky as they could not have been more than a few metres from me

but I could not see nor hear anyone. Clearly

the PAVN’s tradition of exceptional fieldcraft is well maintained today.

Beatrice

Monument

Beatrice

consisted of three hill positions and I had to admit that I had no idea

which one I was on. It must have

been an important one for the Viets to erect their monument there.

Given the general lie of the ground, and the distance we were from

the road, I suspect I was on B4/B2. With

the state of the bush when I was there it would be difficult to go down and

then up again to B1 or B3, I could not see a path but the PAVN boys had got

through. Again this will

probably be easier in the dry season. The

hills themselves are steep and the Viet Minh assault paid the cost.

It was here that Giot died leading the attack and blocking the

loophole of a French machine gun nest with his own body.

In the end though Beatrice fell because of its isolation.

Although closer to the main position than Gabrielle, Beatrice was

more cut off as the hills and jungle closed in around it whereas the routes

to Gabrielle and Isabelle were over flat open ground.

Beatrice was not essential to the defence of

Dien Bien Phu

, if anything it was a relic of the “offensive” role

of

Dien Bien Phu

as an “air-land base” to launch forays of up to

brigade size into the Tai Highlands. Beatrice

was the jumping off point for these raids.

When Beatrice fell on the first day of the battle the French made

only a very half-hearted attempt to retake it.

Gabrielle

Gabrielle

or Doc Lap is easier to get to. You

follow the Piste Pavie, (now the paved Route 12) north out of town.

Gabrielle rises like the Torpedo-boat it was first called.

You have to remember that the French were not comparing it to the

sharp lines of a destroyer but to the turtleback shape of a torpedo-boat.

There are large cemeteries to the NW and SE of Gabrielle and the road

between them crosses Route 12 at the foot of Gabrielle.

There are some small shops and the ubiquitous soup cafes here.

Keep on Route 12 which skirts the western flank of Gabrielle and

about 100 meters north of the shops you will see a path leading off up the

slope. It’s a hands on climb

to begin with but the steepest part is by the road. The

path leads straight up to the monument and you get a great view of the whole

valley. When I was there they

appeared to be planting mulberry trees on Gabrielle, possibly to stop

erosion rather than for commercial reasons.

|

|

Our Hero on

Top of Gabrielle |

From

the top of Gabrielle two things are clear: first what a tough position it

was, secondly how important it was to the defence of

Dien Bien Phu

. Gabrielle

dominates the land around it, and it was the best fortified of the main

positions. It should have been

held and it probably could have been held.

Attacked on the second night of the battle Gabrielle was still

holding out the following morning. A

relief force broke through but garbled messages led the Algerian defenders

to believe that the reinforcements were being sent to evacuate them so they

gave up the hill. If the French

communications had been better the tired but basically sound “Bavowan”

Vietnamese Paratroops would have dug in on top of Gabrielle and the Viet

Minh would have faced the same task again.

Every day that the French held Gabrielle meant one more day of full

air supply as the runway and the drop zones remained clear and the

possibility of air evacuation remained open.

Thus

if the Viet-Minh had not had their “lucky break” on Gabrielle Giap would

have been faced with some hard decisions to make.

Since the losses suffered on Beatrice and Gabrielle anyway obliged

the Viet-Minh to reconsider their tactics and resort to digging and

strangulation over direct assault, if Giap would have had to pay an even

higher price for Gabrielle it is possible that he might have reconsidered

the whole operation, as he did at Na San the year before.

Or, as mentioned in the discussion of Dominique 2, if Gabrielle had

cost another regiment to take the cumulative effect of the meat grinder may

have led to Viet Minh morale decisively cracking after the

Battle

of the Five Hills.

Having

lost Gabrielle the French were in big trouble.

From the top of the hill the valley is laid out before you,

especially the runway and the primary French parachute drop zones used for

reinforcements and supplies. The

flak batteries that the Viet-Minh were able to establish on and around

Gabrielle put a stranglehold on the French Garrison.

Two Roads to the End:

Isabelle

South

from

Dien Bien Phu

proper the valley opens up and it is easy to understand

how the French believed that it was an ideal place to fight a battle of

manoeuvre. The paddies are dead

flat and, although the hills rise to mountains on all sides the feeling is

far less claustrophobic than in the main position.

All-in-all a perfect Devil’s playground for the French armour,

artillery and airpower to smash the infantry of the Viet Minh on.

All the more credit goes to the Viet Minh then for making their

strangulation tactics work on this terrain too.

Fall’s map of Isabelle shows 16 Viet Minh battery positions firing

on the strongpoint and these were not dug into the mountains like those in

the north but somehow concealed on this billiard table.

There are two roads south to Isabelle, the main highway 279 east of

the river and the smaller road to the west of the river.

West

of the river follow the single track road south from the French Memorial.

Once you are clear of the main position this road presumably follows

the route of the old Piste Pavie. It

is very picturesque. You pass

through Thai villages with their thatched long houses and skirt a wide green

sea of rice paddies. Looking out

to the west you can see where Bigeard launched his “flak raid” to

neutralize the Viet Minh AAA on 28th March 1954 and it was from

Isabelle to the south that Lieutenant Preaud’s three “bisons” came

barrelling up across the flat plain to hit the Viet Minh flank and complete

the victory. The raid was a

great fillip to French morale and was the epitome of how they had intended

to fight the whole battle, combining good quality infantry, armour,

artillery and air in a well orchestrated operation.

Sadly for the French Giap gave them little opportunity to repeat such

successes.

East

of the river the main highway provides the quickest route to Isabelle.

Before you get there though you come to the

village

of

Nhoong Nhai

. Here on

25 April 1954

French aircraft bombed a concentration of civilian

refugees, mostly women and children, who had been evacuated from villages

nearer the main areas of conflict. There

is nothing to suggest that this was anything other than one of those ghastly

mistakes that happen in war, not that would be of any consolation to the

victims, or even perhaps to the pilots.

A fair number of French Air Force men were captured at

Dien Bien Phu

and after the battle the Viet Minh made them dig up the

bodies of the women and children and look at them before re-interring them.

It is easy to understand how the Viet Minh felt, and how the French

must have felt.

Today

the site of this tragedy is marked by a simple but striking monument of a

classically dressed woman holding up her dead child in an almost sacrificial

gesture. The monument has not

been well looked after but the slight decay justs adds to the pathos.

It’s a very sad place.

|

|

Monument

to the Bombing Victims |

South

of Noong Nhai lay one of the main reason for Isabelle’s existence ~ the

alternative landing strip for

Dien Bien Phu

. This proved

useless because the main strip was sufficient for all of

Dien Bien Phu

’s needs and the same Viet Minh artillery and flak that

rendered the main strip unusable also neutralised the alternative strip.

The second reason for Isabelle’s existence was that it held one

third of the French artillery which was to provide flanking fire for the

main position. However because

it was so far south of the main position Isabelle’s guns could not reach

the northern positions on Gabrielle and Beatrice so, when the Viet Minh

assaulted these they did not have to worry about neutralizing the artillery

support from Isabelle as well as the main artillery concentration in

Claudine. De Castries was well

aware of this problem and, before the battle started wanted to abandon

Isabelle or replace it with another strongpoint to house the artillery

closer to the main position. But

the false promise of the airstrip kept Isabelle where it was.

The

large marker beside the highway says Isabelle but actually, since you are

still east of the river you are standing at the tip of strongpoint Wieme.

The terrain is perfectly flat and nothing remains of the old

positions which are now covered by a farm and a brick works.

It is a pleasant walk to the river but there is no trace of the

bridge that once connected Wieme with Isabelle proper.

If conditions in the main position of

Dien Bien Phu

were often appalling the conditions on these flat,

flooded, shell shot strongpoints were far worse.

This was “Hell in a very small place.”

Isabelle

was the last part of

Dien Bien Phu

to fall. It

held out because, despite the awful location it was well prepared, with the

best dug outs in the whole valley; its defenders were determined, well they

had nowhere else to go; and although the Viet Minh made several strong

assaults, ultimately they were not prepared to pay the necessary price in

blood to take it. When the main

position was overrun at

5:30 p.m.

on

7th May 1954

Colonel Laland in Isabelle was given permission to

attempt “Operation Albatross” ~ the break out.

This was not the last ditch bayonet charge of Foreign Legion legend

but a two pronged sortie that was quickly intercepted by the Viet Minh.

Although a few made a clean getaway to safety, and more disappeared

in the fire fight or got lost in the jungle clad hills never to be seen

again, most of the garrison fell back to Isabelle in disorder.

At

1:50 a.m.

on

8th May 1954

Laland signalled to

Hanoi

: “Sortie failed. Cannot

communicate with you any more.” The

Battle of Dien Bien Phu had ended.

I

stood beside the

Nam

Yum

River

at Isabelle as the sun went down

alone with my thoughts. It

seemed fitting to end my trip where the battle had ended.

It had been a long trip that had taken me over thirty years.

But finally I had got to go to all of those places that I had been to

so many times before.

go to part two

back to

vietnam

go to part four |