|

DEFCON 3 and Rising . . .

A WWIII “What if” Mini Campaign

by

Peter Hunt

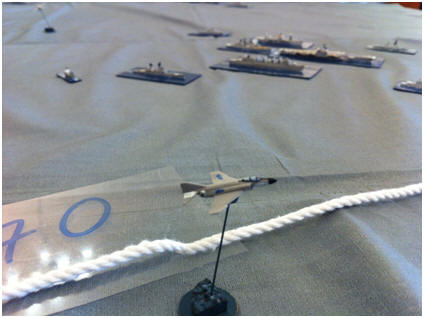

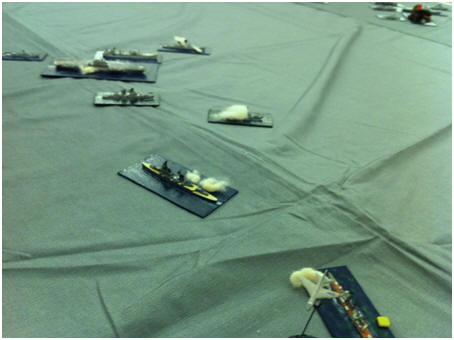

Task Force 60.1 with a Soviet AGI at

the “12 o’clock” position.

The Reality…

On the

morning of October 24 1973, in the final stages of the “Yom Kippur” war,

Israeli troops reached Suez City on the West Bank of the Suez Canal, cutting

off the Egyptian 3rd Army. Egyptian President Sadat requested

that U.S. and Soviet troops be sent to enforce the cease fire that the

Israelis had broken to achieve their encirclement. Secretary Brezhnev wrote

to President Nixon accusing the Israelis of deliberately violating the

understanding reached by the U.S. and the U.S.S.R. and supported Sadat’s

proposal for joint cease fire enforcement, but added: “Let me be quite

blunt. In the event that the U.S. rejects this proposal, we should have to

consider unilateral actions of our

own.”

In the absence

of President Nixon, who was spiraling down into his Watergate debacle and

possibly drunk, Secretary of State Kissinger chaired a NSC meeting that

raised the American strategic defence posture to DEFCON 3 for the first time

since the Cuban Missile Crisis, and for the last time in the Cold War.

Both sides

reinforced their fleets in the Western Mediterranean, including their

amphibious forces. The Soviets closely monitored the American task forces

with “tattletale” surface action groups (KUG) that could coordinate a

distant submarine or aircraft launched missile strike, and, indeed, strike

themselves. With two American carrier battle groups in place and a third

arriving, the Americans had a powerful air weapon. On the other hand the

Soviets were well ahead in missile technology. The Americans had much better

submarines, the Russians had many more of them. It was by no means a

one-sided contest and the Chairman of the American Joint Chiefs of Staff,

Admiral Thomas Moorer concluded that: “we could lose our ass in the

eastern Med under these circumstances.”

America’s NATO

allies were not playing in this game. American Secretary of Defense

Schlesinger considered Ted Heath’s Conservative British Government to be

“quasi-Gaullist”, and, of course, the French were Gaullist:

http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b0137tff#synopsis

Fortunately

for the World calmer heads prevailed and in the real Mediterranean the

crisis dissipated into a gigantic game of “chicken” as the Soviets conducted

anti-carrier exercises against the America task forces, and the DEFCON was

lowered:

http://www.dtic.mil/cgi-bin/GetTRDoc?Location=U2&doc=GetTRDoc.pdf&AD=ADA422490

But in Hong Kong, 38 years later…

“DEFCON

3 and Rising” assumed that the Middle-East War continued, and the DEFCON

continued to rise, until a non-nuclear war broke out in the eastern Med as

both sides moved to support their clients. This involved a day of “non-war”

as both sides jockeyed for position.

The

Soviets decided to launch a massive airlift of troops, backed up by an

amphibious landing to enforce the ceasefire, and insisted that American air

and naval units withdraw from the Eastern Med so that they could not

interfere with this. The Americans stood on their “freedom of navigation”

rights. The Politburo instructed their Mediterranean 5th Eskrada,

supported by Naval Aviation, Frontal Aviation and some PVO Strany units

providing long range fighter cover, to clear the seas and sky above by the

morning of 27th October. The Soviet theatre commanders decided on

a dawn strike. The result of this was several near simultaneous actions: the

“battle of the first salvo”, as both sides struck at their targets and

trailers. Neither side had enough resources to be certain of overwhelming

all of the enemy task forces so it was a question of how they set up their

forces to contact or evade the enemy in “peacetime”, and what resources they

allocated to their attacks.

The game

was designed as another play test for my “Handbrake” modern naval rules that

are under development, and I was hoping for a complex, but cohesive scenario

to develop, involving multiple task forces and missile and air strikes, to

test the rules. Admiral Frankie Li commanded the 5th Eskrada

surface groups (KUGs) and Spetsnaz troops involved in the operation, Air

Marshall Doug Thomson directed the submarine units, (I purposely split the 5th

Eskrada command to make life difficult for the Soviets,) and the air assets

based in Bulgaria, which he commanded from his underground bunker in

Scotland, 6,000 miles away.

Admiral Paul Garnham had his ass on the

line in the Eastern Med, commanding the US 6th Fleet and their

supporting air assets on Crete.

The orders of

battle were built up using the Goldstein and Zhukov article above plus other

sources, with notable help from some friendly chaps on “The Miniatures Page”

site who were actually there:

http://theminiaturespage.com/boards/msg.mv?id=193105

I included the

Israeli, Egyptian and Greek navies in the mix just to keep all the players

distracted but I had little intention of using them, not that that helped

the poor Greeks…

I think

that the naval OBs were pretty close to the real thing, the possible

exception being the number of American attack subs available. I found a

couple of internet sources maintaining that these were there in double

figures, but I limited them to four that I could positively identify… it was

enough. Building and converting the ships became a little bit obsessive, but

that is what wargaming is all about. Aircraft were a different matter. The

carrier air groups were easy to pin down, but I chose

American

F4 Phantoms and Greek F 102 Delta Daggers on Crete because I like them and

wanted to paint them, and most of the Russian aircraft were chosen from what

I had available. I did go on a major converting spree, chopping and puttying

Tumbling Dice 1:600 Yak 25s into the reconnaissance version and Yak 28

bombers and fighters, mainly because I think these are some of the coolest

Cold War aircraft: all pointy and swept back, just like something out of Dan

Dare:

http://www.vectorsite.net/avyak25.html

Strategic

movement was handled by using maps from the great old SPI classic “Task

Force”, and the rest was left to my Machiavellian machinations as umpire.

The War Plans…

The Soviet

problem was coordinating their strikes in space and time, and they had two

main hurdles to overcome. First their Echo and Juliet class missile subs

would have to surface to fire, and, if detected, this would be certain to

set off the Americans. Second the island of Crete gave the Americans a

third, unsinkable aircraft carrier, that also provided radar coverage deep

into the Aegean Sea that would provide them with warning of any incoming

bomber and missile carrier airstrikes on the fleet. In addition to their air

assets the Soviets had spetsnaz units operating off a fish factory ship in

the Aegean and these were given the option of, in order of difficulty,

striking at the main Cretan airfield at Suda Bay, destroying the air defence

headquarters, striking at the airfield’s fuel farm, or striking at two radar

installations on the island. The last were the softest targets, but were

widely separated, so again there would be coordination problems.

The Soviets

decided to hit the fuel farm with spetsnaz just before dawn. At the same

time air launched anti-radiation missiles would strike the radar sites, (if

fact the Egyptian’s had done this at Sharm El Sheik at the beginning of the

Yom Kippur war so I was impressed with Doug’s art imitating life,) followed

by massive fighter sweeps and raids over the airfield and Naval Aviation SU

17s attacking the warships in Suda Bay. Whilst all this was going on the

missile subs would surface and their launch at the American carrier groups

would be coordinated with two strikes by TU 16 Badger and TU 95 Bear missile

carriers, who would be preceded by a Mig 25 fighter sweep, whilst the Soviet

surface action groups and attack submarines got stuck in.

Meanwhile Admiral Garnham spent a frustrating day seeking authority to take

the war to the Soviets before they took it to him, but Washington demanded

restraint. Both his carriers maintained a fighter combat air patrol (CAP) of

Phantoms, and a war at sea CAP of Corsairs during the day and Intruders at

night; whilst his escorts, helicopters and P3 Orions prosecuted several

Soviet submarine contacts near their task forces.

American

nuclear attack boats latched on to Soviet subs, or onto the KUGs, in a

dangerous game of tag, as Soviet ships tailed American ships, and American

subs tailed the Soviet ships. With Soviet Bears, and American E1 and E2

AWACS, having a surveillance range of several hundred miles each, both sides

knew exactly where the other side’s surface ships were and tensions mounted

quickly as Soviet and American ships and aircraft operated in close

proximity. As night fell the Soviet KUGs closed the range to the American

task forces and Garnham released his last reserve: PatDiv 21, four Ashville

class gunboats, two of which were the only American ships armed with

surface-to-surface missiles at the time.

PatDiv 21 en route to the action.

How it played out…

The spetsnaz

raid is described here:

http://fezfamiliar.blogspot.com/2011/12/1973-cold-war-goes-hot-spetznaz-raid-on.html

The airstrikes

on Crete were so one-sided that I played them out as a paper game. The

American Phantoms and Greek Daggers fought bravely but went down under

Soviet numbers, especially after successful Soviet strikes on their radar

removed their ground control advantage. The runway at Suda was cratered, and

the strike on the port left one Greek destroyer sunk and another crippled, a

sad end to Fletcher class ships that had served so well in World War Two.

At sea

we ended up with five possible scenarios ranging from three ships to 27.

Pushed for time before Christmas we focused on the big one, involving the

two main Carrier Battle Groups

of the 6th fleet and played it

out at the 17th December 2011 meeting.

TF 60.2

with

the USS Franklin Delano Roosevelt portrayed here by her sister-ship USS

Midway.

One

hundred and twenty five miles south of Crete Admiral Garnham and Task Force

(TF) 60.1 headed northwest with the carrier Independence, the fleet

flagships Mount Whitney and Little Rock, a missile cruiser, three destroyers

and the huge replenishment ship Seattle. Twenty five miles to his south was

TF 60.2 with the carrier Franklin Delano Roosevelt escorted by one missile

cruiser, three destroyers and an oiler.

Garnham

considered his flag plot and grimaced, it was like the curates egg, good in

part. Both of his task forces had the ubiquitous Soviet intelligence ships

(AGIs) shadowing them. Twenty miles to his west his Sea King helicopters and

a P3 Orion were making life miserable for a Soviet November class nuclear

attack boat. Twelve miles east of TF 60.2 was Soviet KUG 2, consisting of

the big gun cruiser Murmansk and her destroyer escort acting as tattletales.

His own tattletales, Soviet KUG 1, consisting of the cruiser Groznyi and two

destroyers had dropped back and were now 50 miles to his Southeast. Garnham

knew why, the Murmansk would have to keep close to use her 150mm guns but

the Groznyi’s main armament was eight P6 “Shaddock” surface to surface

missiles with a range of hundreds of miles. Groznyi also carried reloads for

her missile, making her more than a one shot threat. However Garnham knew

what the captain of Groznyi KUG didn’t…that Trepang, an American nuclear

attack boat, was shadowing them. Garnham had also vectored the gunboats of

PatDiv 21 onto the Murmansk KUG and they were now thirty miles north of the

cruiser. All this information came to him courtesy of the E1 “Tracer” and E2

“Hawkeye” AWACs aircraft that were tracking all air and surface targets

around his TFs. However he knew that the Soviets had just as good

information, his ESM had no difficulty picking up the surveillance radar

from the TU 95 Rts “Bear D” that was nearly 200 miles to his Northeast.

KUG 2 Shadowing the FDR battle-group.

What Garnham

was missing from his plot was the location of the Soviet missile subs, had

he known where they were he would have grimaced even more. Seventy-five

miles west of him were a line of undetected Foxtrot conventional subs. These

were no threat to his TFs but they were not intended to attack.

Thomsonavitch had put them there as a “trip wire” to engage any American

attack boats heading west, for behind the Foxtrots came his “Sunday punch”:

two Echo class missile boats each carrying eight Shaddock surface-to-surface

missiles (SSMs): carrier killers. To further complicate things for the

Imperialists, a Juliet class missile sub with four Shaddocks was lurking 175

miles to the Southeast.

Just as the

spetsnaz troopers were cutting the wire at Suda, the Soviet missile subs

checked their sonar and blew their tanks to surface. Except, that is, the

Juliet which picked up the distinctive sonar signature of an American Knox

class frigate almost on top of it. Discretion was the better part of valour

and the sub stayed submerged and safe…for now. The two Echos surfaced and

started their cumbersome launch procedures, it would take up to 30 minutes

to acquire targets and launch their birds, and a lot could happen in 30

minutes.

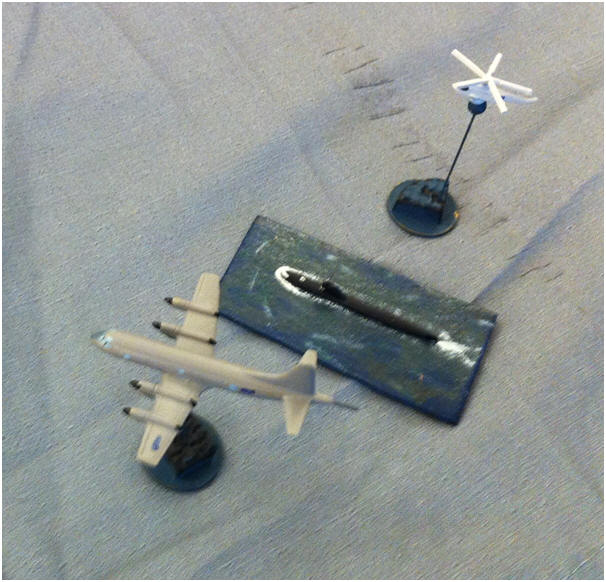

“The Stoof with a Roof” an E1 Tracer

AWACS.

Garnham

was well served by his AWACs’ unblinking eyes in the sky. Detecting the

relatively small surfaced subs was not certain at such long range but both

were picked up. This triggered the 6th Fleet’s rules of

engagement, they need wait no longer for proof of Soviet aggression and had

permission to fire in self-defence. The first to suffer were the Soviet AGIs

which had been shadowing both TFs, unarmed, but still potentially deadly as

they would act as homing beacons for the rest of the Soviet forces, they

were quickly dealt with by a combination of American SAMs used in the

anti-ship mode, and good old fashioned 5” gunfire. The rest of the American

pre-emptive response was less effective. After tracking the November for

hours, the Sea King was finally given “weapons hot” permission, only for the

crew to watch in dismay as their torpedoes either failed to home or were

evaded as the November sprinted towards TF 60.1. The two “war at sea”

air-strikes were equally ineffective. The four Intruders targeting KUG 1

were quickly acquired and faced a barrage of missiles from Groznyi and her

consort, the Kashin class air-defence destroyer Povornyi, and lost one of

their number without scoring any hits. The Intruders targeting KUG 2 only

had to face one Kashin class and suffered no losses, but likewise scored no

hits. Garnham had no time to curse his luck as the flag plot started

lighting up with incoming Soviet strikes…this battle was going to be short,

but desperate.

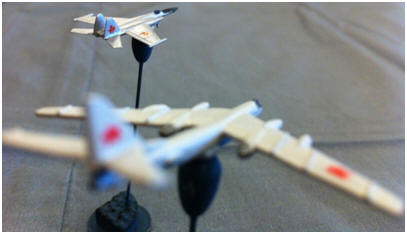

“Defender of the Fleet”: The “Horizon

Cord” shows that, in game terms, this F4 Phantom II CAP is at least 70 miles

outbound from TF.60.1 in addition to the separation on the table.

First to

arrive were the fastest fighters in the world: six Mig 25s. These were

intended to engage the American CAPs to clear the way for the bombers

behind. However the Mig 25s were designed for reconnaissance, or for

intercepting enemy bombers with their long range missiles, hence their high

speed. In a dogfight they were at a big disadvantage, having no short range

missiles or cannon whilst the defending Phantoms had both. Thus, after a

long range exchange of Soviet R 40 and American Sparrow missiles that

accounted for one aircraft each, the Soviets could do nothing more than to

use their speed to “bug out” before the Phantom CAP closed. If numerical

honours were equal the CAP had held the fleet’s defence perimeter and so had

a tactical victory. But they had no time to gloat... the Soviet bombers were

inbound.

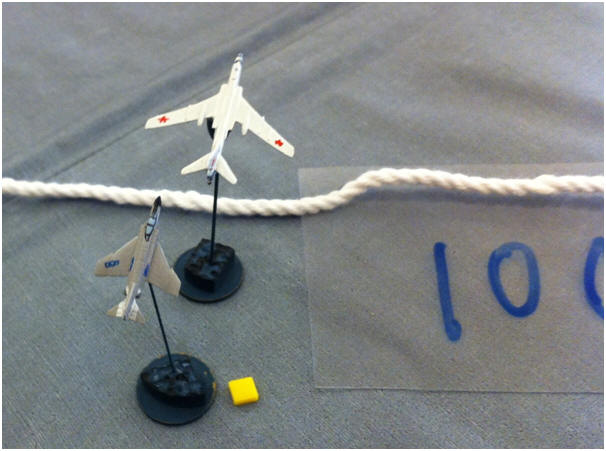

Mig 25s inbound touch base with the

TU 95 Rts Bear surveillance aircraft.

The first

strike consisted of 6 TU 16 Badgers and 2 TU 95 Bears, all armed with a

brace of air-to-surface missiles. The TU 95s were unable to datalink with

the Bear D spotting for them and made a flyby to try a second approach. The

Badgers had no problem obtaining target information and twelve KSR 2M “Kelt”

missiles were soon heading towards TF 60.1. Garnham viewed his flag plot

apprehensively as the transonic missiles, the size of small planes, were

picked up by the AWACs and the Task Force’s own radar. The second CAP flight

engaged with their Sparrows and splashed three of the missiles and the

ships’ missiles accounted for two more. Again the Soviet electronics let

them down as half of the missiles failed to receive the necessary mid-course

guidance from the Bear D, but the remaining ones locked on to a large target

near the centre of the Task Force… moments later the supply ship Seattle was

devastated by two massive explosions as the Kelts hit home.

The Soviet AGI burns on the

horizon as Kelts smash into the Seattle, but the Independence and the 6th

Fleet Flagships are untouched.

The

second strike of 10 Badgers was targeted at TF 60.2.

Again only one flight succeeded in

datalinking with the Bear D and launched 10 Kelts. The other flight pressed

home the attack anyway hoping to acquire targets with their own radar as

they got closer. This was a brave move…brave but foolish. Although their

Sparrows were expended the two Phantom CAP flights still had plenty of

Sidewinders and 20mm ammunition and the hapless bombers were easily taken

down before they could get a radar lock on any American ships.

Bad Day for the Badgers: Few TU 16s

managed to break the 100 mile line.

As the Kelts

homed on the Southern Task Force the FDR’s escorts put up a barrage of SAMs,

and again the Americans were helped by a failure of many of the missiles to

pick up the mid-course guidance that they needed, but still Kelts came on,

their radars seeking targets. One picked a target at random and smashed into

the superstructure of the missile cruiser Yarnell, the other missile headed

straight for the flat-top. The missile struck FDR high on the rear of the

“Island” destroying her radar but not critically damaging the ship, although

flying operations would be hampered… a lucky escape.

Meanwhile the

November was sprinting towards TF 60.1 and loosed a spread of torpedoes at

the closest target, the destroyer Sampson. The American detected the noisy,

fast sub, and also the torpedo launch and turned to comb the tracks. As the

torpedoes ran harmlessly along-side, Sampson retaliated with her own ASROC,

dropping a rocket-borne homing torpedo on top of the Russian boat. The

Soviets were making too much noise to hear the torpedo entering the water

above them, but there was no mistaking the sound of the explosion near the

November’s stern, jamming her steering. To make a bad situation worse the P3

Orion that had been stalking her passed up the opportunity to pursue the

Echoes far away off to the west for the surer target of the November, and

another near miss from a MK 44 torpedo took her turbines temporarily off

line.

ASW: P3 Orion and Sea King hound the

Soviet November attack boat.

The other

submarine in the battle, the U.S.S. Trepang was no more successful, she

attempted a difficult stern shot at the Groznyi, and missed, just as the

cruiser launched eight “Shaddock” missiles at TF 60.1. Once again SAM fire

and inconsistent mid-course guidance whittled down the numbers but three

missiles locked on to one of the largest targets in the battlegroup. And

once again it turned out to be the hapless Seattle which suffered another

hit and two near misses. The crew of the Independence looked on with a

mixture of horror, and relief that it was not them, as the huge supply ship,

critically damaged and burning from end to end, settled in the water.

With a brief

respite both carrier groups turned into the wind to launch aircraft. The

battle would be decided in the next minutes. As the Intruders and Corsairs

made for their targets and the Phantoms replenished the CAP, the Soviet vice

tightened. From the northwest the Bears roared in again, to the west the

Echoes were ready to launch and to the southwest the crew of Groznyi were

rushing to reload her cumbersome SSMs, whilst the Murmansk headed for TF

60.2, which could either run, or launch aircraft, but not both.

The Bears

proved the easiest threat. This time they had no trouble data-linking and

launching, and the missiles picked up the mid-course guidance, but with only

four in the air the revived CAP and the missiles of the Independence’s

escorts easily dealt with them.

KUG 1 was

equally unlucky. Before the Groznyi’s missiles could be reloaded the

Independence’s bombers thundered in. A barrage of SA-N-3 Goa missiles

accounted for three of her attackers but the Americans drove home, leaving

the Groznyi a burning wreck, stopped in the water. Whilst the naval aviators

of the U.S. Navy had done the heavy lifting the submariners were not to be

denied their prey either. With a sitting target the Trepang did not miss a

second time, breaking the Groznyi’s back and sending her to the bottom.

Intruders and Corsairs devastate the

Rocket Cruiser Groznyi.

So everything

depended on the Echo subs’ Shaddock SSMs. The FDR’s CAP, not distracted by

bombers, quickly homed on the salvo heading for TF 60.2 and dealt with five

of the eight missiles. As the Phantom’s broke off the destroyers Ricketts

and Dewey engaged with Tartar and Terrier SAMs. The incoming SSMs were all

accounted for but the last one was so close to the flat-top that debris

followed through, causing minor damage and wiping out some exposed damage

control teams, but not endangering the carrier or her operations. As the FDR

ran into the north-easterly wind to launch aircraft the Murmansk closed on

her. Corsairs and Intruders harried the Russian cruiser and her consort the

destroyer Smetlivyi. These were followed by Standard SSMs from the two

Ashville class missile boats of PatDiv 21. The Smetlivyi suffered badly and,

although the Murmansk’s armour saved her from critical damage she suffered

many minor hits and was unable to break through to the carrier, being

satisfied with wrecking the destroyer Ricketts with her 6” salvoes.

Old School: Murmansk engages the FDR

battle group with gunfire whilst the Corsairs strike back.

The last eight

Shaddocks headed for TF. 60.1. The overworked CAP accounted for only two of

the incoming SSMs and the area defence missiles another two. The surviving

groups of three and one missile sought their prey and locked on to a large

target near the centre of the group… the already burning hulk of the

Seattle. As the giant supply ship reeled and finally sank under this final

onslaught the Independence had, once again, been saved by the vagaries of

Soviet targeting technology.

The Final Agony: Yet more Shaddocks

smash into Seattle whilst Independence remains unscathed.

Aftermath…

We called the

game at this point. The Americans still had more aircraft to launch whilst

the Soviets had run out of missiles and their cruel luck had already lost

them “The Battle of the First Salvo.” A hit and a near miss had caused only

relatively minor damage on the FDR, and, by rights, half of the nine

missiles that had homed on Seattle should have gone for Independence

instead. It was probably well that Air Marshal Thomsonovich was not present

to personally witness Admiral Li’s dice rolling, as a collateral, vodka

fueled, altercation would have only added to the damage the Soviets

suffered.

The mini

campaign format had proved fascinating for me as the umpire and frustrating

for all three participants who had neither the resources, nor the

flexibility, to do everything that they wanted, and thus had to make hard

choices. Nevertheless both sides had developed workable plans and the final

situation that developed, and that we played out, was finely balanced and

could have gone either way.

“Historically”

the scenario captured a moment in time when the naval contest between the

two superpowers was truly “in the balance.” The second generation Phantoms

were still reasonably effective against the first generation Shaddock SSMs

but would have been overwhelmed by the second generation ASMs and SSMs that

arrived a few years later. The Echo class boats were soon superseded by

Charlie class subs that did not have to surface to fire their SSMs, (indeed

one of these was off to the east, preparing a nasty surprise for an American

Amphibious Group.) And on the American side within two years the

introduction of the F 14 Tomcat with long range Phoenix air-to-air missiles,

followed by the introduction of air and surface launched Harpoon anti-ship,

(and anti-surfaced-sub,) missiles would begin to swing the balance back in

their favour.

The two

players had handled 18 US surface ships and seven Soviets, plus an attack

sub on each side, and the two Soviet missile boats. In the air 44 American

aircraft of all types, (with more to come,) had faced 25 Russians. Forty

minutes of game time had taken three hours on the table-top. So I was well

pleased with the playability and accuracy of the rules compared to the

industry leaders such as “Harpoon” and “Shipwreck”, but the game threw up

lots of ideas for further streamlining to increase playability without

sacrificing accuracy, and I’m working on them now.

I’d like to

thank Paul, Frankie and Doug for their commitment to the project, good

humour, and practical feedback. All that they asked for was “A Willing Foe

and Sea Room”, and they got both…

“Willing Foes”: Admirals Li and

Garnham contemplate their next move whilst the umpire ponders another round

of rules rewriting.

back

to other periods

|