|

|

|||||||||

|

|

NINE FATHOMS DEEP IN IRONBOTTOM SOUND

The First Naval Battle of Guadalcanal Re-fought with “Nimitz” Rules

By Peter Hunt

0142hrs: “Enemy in Sight! Red Oh Two Oh. Range 3000.”

“Illuminate with Star Shell!”

The Set Up

Readers of my review

of Sam Mustafa’s WWII naval rules “Nimitz” will know that I consider

them a flawed masterpiece. I use that artistic description

intentionally, for in a more perspicacious, and much shorter, review

than mine Charles Vasey, for whom I have always had massive wargaming

respect, uses an artistic analogy that the rules take an ‘…

impressionistic approach (“We paint not light, but the impression of

light”)... ´ His phrase struck a chord with me because, as a lad, when I

was not wandering around the Cardiff Central Library ascertaining the

barbette armour of HMS Anson, I was wandering about the National Museum

of Wales which has a marvellous collection of Impressionist art. One of

the important things about Impressionism is that it is not abstract.

Monet might have painted Rouen Cathedral over 30 times each with a

different impression of light, but each time he painted it the subject

was still, clearly, a cathedral.

Putting my money where my mouth is I had already

drawn up a draft set of amendments to see if we could cure Nimitz of

what I considered its flawed bits, named, from the other side of the

pond, “Cunningham,” (included here in their final form, not the interim

version used in this playtest.) Get the midshipman to bring you a nice

hot mug of naval cocoa - Kai, (or Kye, spellings vary,) peruse them, and

feel happy to use any that you see fit.

[hyperlink to follow.]

The major changes include halving the length of

the turn, revising the torpedo and night-fighting rules, enhancing the

special effects, and minor changes to the gunnery. The changes seemed

sensible, but did we still have a work of art? And just as importantly,

could we still see the cathedral? A playtest was in order, and it is

always my belief that if you want to find out if a set of rules is up to

snuff, then a historical playtest is in order.

Tony, with his usual speed and efficiency, (I’m

sure he has a sweat shop in his back room, no one can possibly paint

stuff as quickly as he does,) had produced both sides for the Battle of

Midway in 1:6000 scale using Figurehead miniatures and Litko bases. This

enabled me to put together the historical OB for the First Naval Battle

of Guadalcanal on 13th November 1942. All the class types were correct

except that Tony didn’t have a Brooklyn class “machine gun cruiser” so

the CA Northampton had to impersonate the CL Helena. Out of the 27 ships

in the battle 16 were as named and the other 11 were represented by

ships of the same class, so I have used the latter’s new names in this

account rather than the original historical names.

Tony played Rear Admiral Daniel J. Callaghan

commanding Task Force 67 consisting of two heavy cruisers, three light

cruisers, and eight destroyers. Bill was Vice Admiral Hiroaki Abe with

two fast battleships, one very light cruiser, and 11 destroyers. In

Nimitz points values the Americans had a 10% advantage with 107 points

against 98 Japanese. This was only Tony’s and my second Nimitz game, and

Bill had never played before, so it was a good test to see if we had

retained the simplicity and playability of the basic Nimitz rules whilst

enhancing their historical accuracy. I don’t think that either admiral

knew enough about the historical action to affect their responses,

indeed Bill’s favourite feature of the Guadalcanal Campaign was that

when HMNZS Kiwi rammed the Japanese submarine I-1 the Japanese officers

replied with swords. Clearly there would be no lack of samurai spirit

from a man of such tastes.

The Game

Both sides received a historical briefing. It was

a dark night that had seen heavy rain, with no moon. Visibility was

about 3,000 yards. The south side of the table was the northern coast of

Guadalcanal, and thus impassible. Abe could form his squadron into three

columns. His aim was to reach the south-east corner of the table whence

he could bombard Henderson Field. To this end his two battleships had

their guns loaded with, and their ammunition hoists full of,

“Sanshikidan” air-bust shrapnel ammunition. Whilst very effective

against planes and unarmoured structures these shells were much less

effective against armoured targets, and it would take several salvoes to

fire them off before the guns could reload with armour-piercing rounds.

Because of a heavy rainstorm Abe had circled his squadron to use up time

and let the rain squall precede him so that he could bombard Henderson

in the clear. Abe had put is squadron into three parallel columns, one

with the light cruiser Nagara leading the battleships Kirishima and Hiei

(flag), followed by destroyers in the centre; and then a column of

destroyers on either flank.

Bill chose three columns of destroyers,

with the columns led (from south to north) by Nagara, Hiei and

Kirishima.

Callaghan’s Flagship San Francisco had been hit in

a bombing attack the day before and had suffered structural damage and

had its radar knocked out.

A Japanese attack that night was

anticipated, but it was not known whether this would be directed on

Henderson Field as had happened a month earlier; or against the American

supply ships that had sailed east from Guadalcanal that evening; or be

in support of a troop landing. Callaghan had to guard against all three

possibilities. With limited command and control capabilities, doctrine

required Callaghan to field TF 67 in one column. Callaghan put

destroyers in the van and rear of his line, with the cruisers in-between

and the San Francisco (flag) in the centre. Tony did the same.

Thus, in the early hours of 13th November 1942,

four columns of ships were sailing on parallel courses off the coast of

Guadalcanal. The Americans were closest inshore, heading north-west,

whilst further out were the three Japanese columns led by Nagara, Hiei

and Kirishima respectively, heading south-east. With no radar on his

flagship Tony was reliant on the other radar equipped ships of his Task

Force to see for him – a most inefficient arrangement. It was Helena who

gave the first warning, reporting a contact 14 miles off her starboard

bow at 0124hrs. Whilst Tony was digesting this information the other

radar ships reported their own contacts, but blocking each other’s

transmissions on the Talk Between Ships, (TBS), and giving relative

bearings rather than true ones, which without a Combat Information

Centre to collate and plot all this information left Tony with little

more spatial awareness. With the contact closing at a mile a minute,

(and we were using six-minute turns) Tony ordered a starboard turn for

his line to the north which would “cross the T” of the contact.

Callaghan has done the same.

For his part Bill had no radar to tell him what

was in the offing, but he could trust to his squadron’s superior optics,

hand-picked lookouts, and well-drilled night-fighting skills to give him

the edge and sight the enemy before the enemy sighted him. But a

battleship is a much bigger target to see on a dark night than the lead

American destroyer, so their sightings were almost simultaneous at

0142hrs. A rather shocked USS Ducan reported a battleship 3,000 yards

away and was ordered to illuminate the target with star shell.

The refight of the First

Naval Battle of Guadalcanal had begun.

With his advantages in night-fighting Bill was well placed to win, and

go on winning, the initiative. But having done so he was faced with the

Nimitz dilemma of moving first or second, and thus giving the enemy the

chance of reacting to his moves, and then firing first or second, when

firing second may be too late. He had no idea what the enemy forces were

but had clearly put his battleships to the fore for a reason, so opted

to swallow the disadvantage of moving first for the promise of shooting

first.

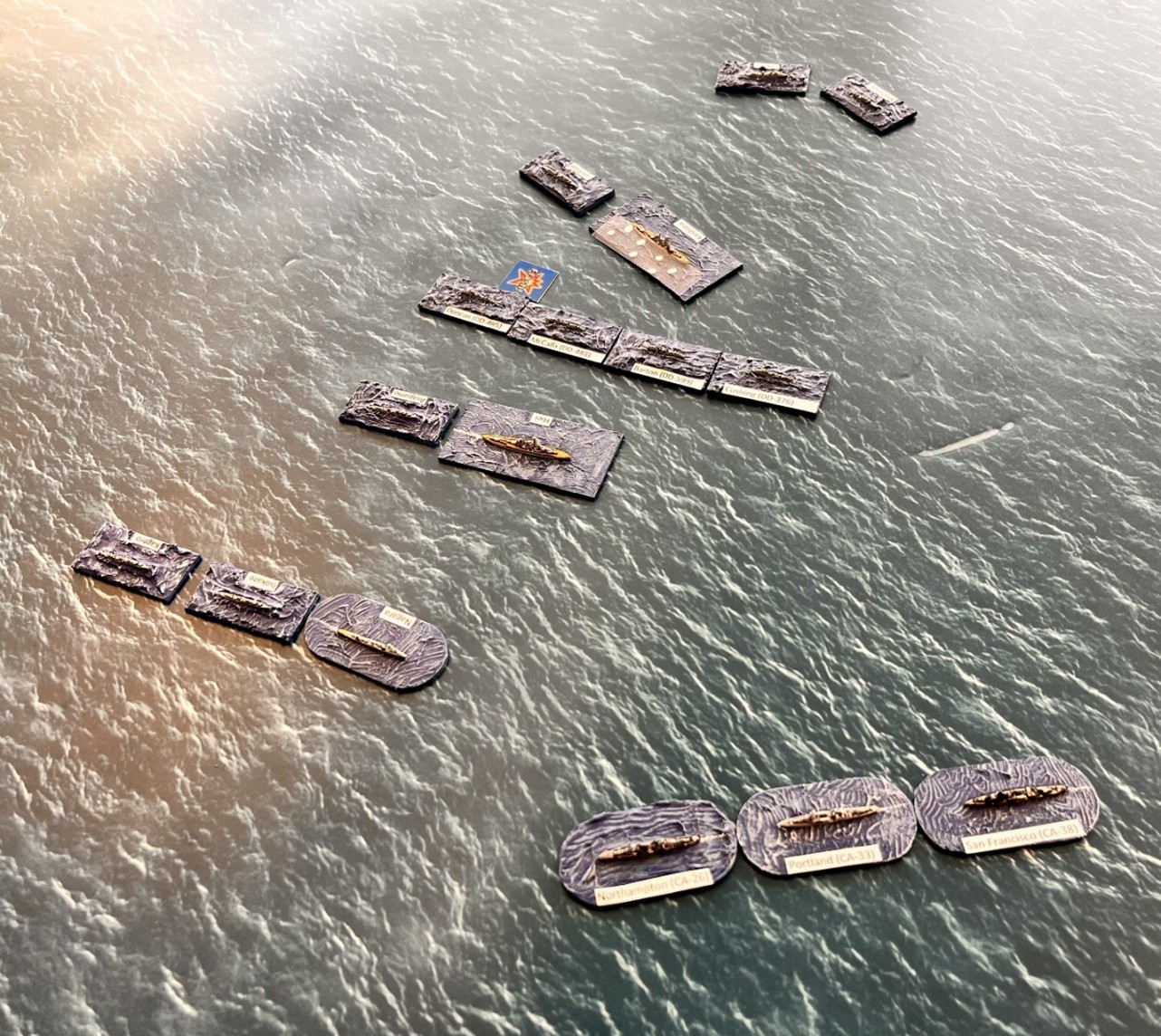

0142hrs: The Plot Thickens (See what I did there?) Duncan has illuminated Kirishima. The situation before the Japanese move. Admiral Abe realises that his formation is not as neat, nor compact, as he had thought . . .

Normally in Nimitz sides alternate moving

individual ships or groups of ships, starting with the slowest and

progressing to the fastest. Since in this first on-table move all ships

happened to have the same speed on and the Americans were in one, still

predominantly unseen, group, I put my umpire’s cap on and got both

admiral’s intentions before moving what ships could be sighted for them.

It was only now that Bill realised that his neat formation, with three

columns advancing on a level front, had been disrupted when he had

performed that loop in the rain squall and had broken up into four,

unevenly spaced columns with Kirishima well to the fore. (Abe had faced

a similar problem). Nothing daunted the Japanese turned to engage and by

closing the range sighted three more American destroyers behind Duncan.

0148hrs, the Japanese turn to engage and sight McCalla, Barton and

Cushing behind Duncan. The Americans only have sight and firm radar

tracks on the heads of the Japanese columns, in the darkness and

confused radar echoes are five more unseen Japanese destroyers.

To Tony it appeared that he had a numerical advantage with 13 ships to

nine, so a close-range knife-fight seemed a good proposition. The

leading American destroyers could have turned away, but Tony threw them

into the melee just as Callaghan had done before him. Unlike Callaghan,

who followed his destroyers with his cruisers in-between the Japanese

columns, issuing the unusual order: "Odd ships fire to starboard, even

ships fire to port” Tony turned his cruisers sharply to port to bring

their starboard arcs to bear on the Japanese outside column.

0148: Before the Guns Speak

Duncan has led the American destroyers in between

the Hiei’s (flag) and Kirishima’s columns. If the destroyers survive

they will be well placed to end the battle in six minutes with torpedo

attacks on the Japanese battleships. To the south the 6” cruiser Helena,

(portrayed here by Northampton,) followed by the 8” heavy cruisers

Portland and San Francisco (flag) can engage the Nagara but cannot see

Hiei. Behind the San Francisco are two more light cruisers and four

destroyers, as yet unseen by the Japanese.

Bill’s decision to move first and thus fire first seemed to pay off. In

the real action some of the American destroyers had passed so close to

Kirishima that the battleship could not depress its guns enough to

engage them. On the other hand, the destroyers were too close to use

torpedoes. In this re-fight the three lines were separated by at least

1,000 yards each, so the battleships had clear shots, but any surviving

destroyers would have perfect targets for their, albeit very unreliable,

torpedoes.

There was to be no torpedo attack. In Nimitz both

sides alternate firing individual ships or groups of ships. Hiei and

Kirishima opened-up with their 6” secondaries and then Kirishima and her

consort destroyer added their 14” and 5”, to boot.

Duncan was crippled and McCalla sunk by

this onslaught. In reply the plucky Cushing hosed Kirishima’s upperworks

with 5” shells, damaging her directors which would debilitate her fire

for the rest of the battle. As the other Japanese groups joined in,

Ducan was finished off, Hiei sank Barton, and Nagara zeroed in on

Cushing’s gun flashes and sank her. The battleships’ Sanshikidan shells

would have been deficient against armoured targets, but they were more

than adequate to deal with the “tin can” hulls of the destroyers.

0148hrs: The Battle Opens Well for Abe

Duncan is crippled and McCalla sunk. Barton and Cushing have replied

with their 5”. Hiei and Nagara are about to finish the job.

From Callaghan’s column only the lead ships of the Nagara column were

initially in sight, but when Hiei opened-up with her secondaries the gun

flashes gave the American cruisers an aiming point and they used their

own 5” secondaries to illuminate the battleship with star shell. (So,

there can be benefits to firing second). As the star shell hung over

Hiei like chandeliers, the three cruisers had a clear target and all

shot well. Helena struck Hiei’s forward barbette. At this range there

was an outside chance of a 6” shot penetrating the 10” of armour – but

it was not to be, and the shell inflicted little damage. Portland struck

Hiei’s superstructure and knocked out her main director. But, when San

Francisco fired that strange magnetism that attracted Helena’s fire was

still working, and another hit on Hiei’s magazines was scored – this

time the 8” shell punched through, (it was about 5,000 yards away and

could have gone through 10” of armour at 9,000 yards.) So ended the

Hiei’s and Admiral Abe’s participation in the battle.

0148hrs: That Strange Magnetism. Abe’s Battle Ends Abruptly

“The Hiei’s Gone…”

“…Where?”

Word of the loss of the flagship was passed

through the Japanese squadron with a sort of whispered incredulity and

was received with incomprehension by those below decks who had not

witnessed the explosion. In game terms, with Abe nine fathoms deep in

Ironbottom Sound[1]

the Japanese command and control problems had cancelled out their

night-fighting advantage for the initiative test, and the Americans now

held a marked heavy gunnery superiority. For the only time that night

Tony won the initiative and, with his line in perfect order opted to

move first to maximize his gunnery advantage by shooting first.

As

the groups on both sides alternated movement and emerged from the

darkness into the flames and the smoke of battle, for the first time

both commanders were finally able to judge the odds against them. The

Americans still had two heavy and three light cruisers, plus four

destroyers, the Japanese one battleship, one light cruiser, and 11

destroyers.

0154hrs: Before the Deluge

The American line at the bottom is led by five cruisers, followed by

four destroyers. At the top left Kirishima has reversed course to

avoid being a torpedo magnet for the American destroyers, whilst the

light cruiser Nagara (almost dead centre, leading the bottom

Japanese column,) and ten destroyers sail into harm’s way.

Tony issued the clear, if a trifle redundant,

order: “All ships open fire to starboard!” The Americans were in a

perfect gunnery position, with all their “A” arcs open and two

Japanese columns within 2-3,000 yards. Eighteen eight-inch, 15

six-inch, and no less than 60 five-inch, (almost half of which were

contributed by the 14-gun broadsides of the light cruisers Atlanta

and Juneau,) guns belched forth their broadsides. Against this the

Japanese could only initially bring to bear 6 six-inch and 36

five-inch guns, with a handful of five-inch joining in later firing

at the Americans’ gun flashes. San Francisco and Atlanta smothered

the light cruiser Nagara with fire and sank her, the American

destroyers dispatched the destroyer Asagumo leading the second

Japanese column; and Helena and Juneau, (first and fifth in the

American line), set their opposite numbers on fire, and others

received lighter damage. When the surviving Japanese ships tried to

return the compliment they had little obvious effect, although a 5”

shell exploded in Helena’s boiler room intakes temporarily reducing

her speed.

0154hrs: Broadsides! Commence, Commence, Commence!

Ninety-three American guns pour fire into the Japanese lines.

Nagara and Asagumo leading the Japanese columns are sunk, Sazanami

and Takanami, (the latter not yet marked,) are set on fire. Others

are damaged but not crippled. It is a tribute to the way that the rules were playing that both Tony and Bill had fully entered into the spirit of this rather strange, decidedly hectic, and disturbingly sudden-death, night action. The Americans had, as is their wont, taken guns to a knife fight. If the point-blank exchange of gunfire continued like this there would be little left of the Imperial Japanese Navy. For their part the Japanese were out to prove, as is their wont, that the battle was still a knife fight, to be decided with knives, or at least Long Lances. It was not difficult to imagine the Japanese destroyer commanders turning their eyes from the sight of Nagara being destroyed ahead of them, brandishing their swords, pointing right, and ordering their 24” torpedo tubes to train to starboard…

The Type 93 torpedoes were still pretty much

of a mystery to the USN at this stage in the war, but what mattered

most in this engagement was not their long range, but their high

speed and heavy warheads.

Fired from the optimum position –

forward of the target’s bow but not in a small aspect - eight

quadruple spreads of Long Lances closed the American cruisers at a

combined speed of over 70 knots, and stopwatches on board the

Japanese destroyers were set for 80 seconds.

0201hrs and 20 seconds: The Night of the Long Lances

From left to right Helena, Portland, San Francisco, and Atlanta are

cut down by 24” torpedoes.

From the bridge of the Juneau, the fifth ship

in the American line, it seemed as though the Pacific Ocean has

erupted in a paroxysm of explosions and fire, as every ship ahead of

them had their backs broken by the Long Lances. Admiral Callaghan

joined Admiral Abe nine fathoms deep in Ironbottom Sound. Further

down the battle lines more destroyers were adding yet more “fish” to

the mix, with the Americans targeting the damaged Takanami, and the

Mochizuki aiming at the Aaron Ward.

These torpedoes would take six minutes

to run, and that night in Ironbottom Sound a lot could happen in six

minutes.

Putting her helm hard to port Juneau led the

American destroyers south towards the coast of Guadalcanal, hoping

that the Kirishima would not follow, but the Japanese had the bit

between their teeth and turned south too. The American gunfire was

still potent, Juneau and Aaron Ward sank

Isokaze, and Buchanan sank Kagero. But Juneau’s gun flashes

disclosed her position to the Kirishima, which, firing by local

control, exhibited remarkably good shooting in these debilitating

circumstances and brought down a hail of 14” shells on the light

cruiser, crippling her.

0205 hrs The Run South

American gunfire sinks Isokaze and Kagero, but Juneau, exposed by

her own gun flashes, is targeted by Kirishima on the extreme left.

The blue datum markers show where the Japanese and American

torpedoes were lunched from five minutes ago. They still have 60

seconds left to run. On board three destroyers men watched as, with what seemed to be agonizing slowness, the hands of stopwatches and chronographs ticked down the seconds from 360 to zero. From the south there came a flash, followed 25 seconds later by the sound of a crashing explosion as the USS Aaron Ward disintegrated. To the west there was no flash and no sound. The chronographs ticked on – 390 seconds, 420 seconds – the American torpedoes had missed. (In game terms torpedo shots at these ranges and aspects had only a 1-in-6 chance of hitting, so with four American and two Japanese spreads in the water only one hit was par for the course. But, again, the torpedo gods had chosen to smile on the Japanese this night).

As

the torpedoes sank to the bottom of Ironbottom Sound the guns

continued to thunder in a final paroxysm of death and destruction as

both sides ran south towards Guadalcanal. USS Farenholt sank

Urakazi, and, for the last time that night, Kirishima found her

target and sank the Lardner. By now however Kirishima was

approaching the five-fathom line – a matter of some concern since

she drew 31 feet of water. Bill turned north-west, and Tony

south-east. Just after 0212 hrs the refight of the First Naval

Battle of Guadalcanal had ended.

Some Conclusions, Some Thoughts, and Some Tweaks

I was a very happy little bear….

The rules amendments had worked well, I think Bill and Tony had had

a good time, (or as good a time as you can have when you have four

cruisers shot out from underneath you in one turn), and although the

refight was different to the historical fight we had not exceeded

the bounds of historical possibility and nothing ahistorical had

reared its ugly head.

The real battle had lasted about 40 minutes

and our seven turns added up to 36 to 42 minutes, so spot on there.

This had taken about two and a half hours of play, so about 20

minutes a turn. This is slower than the “real time” aimed for in the

Nimitz RAW, i.e. a 13-minute game turn played out in about 13

minutes, but it is difficult to see how this historical match-up

would have worked with the RAW at all. Both sides would have been in

clear vision at 13,000 yards, (12”). There would have been no

deductions for gunfire effect, although there would have been fewer

chances to fire. Torpedoes would have been (even more) devastating,

hitting instantly at 12” with no deductions for range. With both

sides closing the 12” sighting distance at a maximum of 24” a turn,

(in fairness, more practically a 16”+ closing speed), anything still

afloat after the first turn would have passed the opposing ships and

spent the next two turns to turn 1800 to re-engage. It

would have been quick, and very bloody, and could well have been all

over in real time of three 13-minute turns played out in 40 minutes.

But it would probably not have had the historical feel, nor given

the satisfaction of the revised rules. The revisions are aimed at

maximizing Nimitz’s good points – interactive movement with no

pre-plotting, and a clean, innovative, gunnery system – whist doing

away with some of the simplifications that reduce the game to a

dice-fest of bumper cars at sea. As it was, with the revisions, Bill

and Tony were constantly being called upon to make interesting

decisions about what to do and how to do it, and that, to me, is the

essence of a good game.

We had a higher casualty rate than the real battle, but that is not

unusual in wargames. Yes, by halving the move time, and adding the

point-blank rule, (and a lot of this game was fought at point blank

range because of the nature of the historical battle,) the

effectiveness of gunnery has been increased over the RAW, but I

think that the two main contributory factors to the ship-killing

were the lack of confusion, and the torpedoes.

Confusion is hard to do in a wargame, unless you want it to descend

into random anarchy, which might be accurate, but is not much of a

game. We were playing in an air-conditioned room, after a nice lunch

with a bottle of wine. Most of the ships were in clear view, even

though they were not within “sighting” distance of each other, and

they would always go where they were ordered to go. To model the

confusion of the real battle I should have put Tony in a dark metal

box, hit the outside with sledgehammers, fired strobe lights in his

eyes, let off fireworks near his trousers and had him shout out

orders to ships from memory of where they were supposed to be.

Appealing as so torturing Tony in pursuit of wargaming excellence

this might be, the more practical wargaming answer is to tweak the

rules to add a bit more confusion by catering for friendly fire, (a

continuing factor in Pacific night actions right up to Surigao

Strait, in our historical battle, for example, San Francisco

clobbered Atlanta), derelicts, and collisions. There would be more

hazards to navigation if there were less ships sunk immediately, and

more ships becoming stopped or manoeuvring erratically to break up

the neat groups. This brings us to the torpedo effects.

The power of the Long Lances to sink ships

immediately is not a rules accident. Mr Mustafa discusses this on

page 36 of the RAW. As the rules stand, they have a 50% chance of

immediately sinking a heavy cruiser, a 66% chance of sinking a light

cruiser, and will automatically sink a destroyer. So, on this basis

Bill’s performance of sinking three out of three heavy cruisers,

(Helena has the same protection as a heavy cruiser,) amounted to a

one-in-eight chance, difficult but far from impossible. The odds

were further stacked against Atlanta, and once Aaron Ward was hit

she had no chance of surviving.

Unfortunately, the real-life odds do

not stack up that way. This list gives combat damage to American ships in WWII and from it you can extract the ships hit by surface launched Japanese torpedoes. If you want to be more complete you can add in the ABDA ships that suffered the same fate, (one heavy cruiser, three light cruisers, and some destroyers).

Of the 11 heavy cruisers, (including Helena

and Exeter,) hit by Long Lances, only three were sunk immediately,

three others were eventually sunk taking between 50 minutes and

three hours to go down, (I include Exeter in this, as rather like

Bismarck she was in the process of scuttling herself when the

torpedoes hit,) and five survived.

Of the five light cruisers, (including

three ABDA ships,) two sank immediately, one took three hours to go

down, one was scuttled the next day, and one survived. Of the 14

American destroyers hit, for seven it was not an instant death

sentence. Three survived to fight again, and the other four survived

for between 81 minutes and a month before succumbing to their

wounds. (My favourite is the USS Chevalier, the 81-minute case,

which had its bow blown off by a Long Lance, was then rammed in the

stern by a friendly destroyer, and still managed to fire torpedoes

and sink a Japanese destroyer before she went under herself.)

Clearly Nimitz’s Long Lances are a little overrated. They should

still be better than other nations’ torpedoes, but a reduction in

strike value from 5 to 4 will achieve this. The amendments give the

warhead weights, which go along with the justification for a 3 to 4

rating for British and Japanese torpedoes, (I appreciate that if you

used the square of the warhead weights that would give you a 3 to 5

ratio, but I think that using squares to determine effect is the

sort of thing that you would find in rules by Fletcher Pratt, not

Sam Mustafa). Whilst looking for unintended consequences in the rule

change, I found that the Italian and French torpedoes are already

rated at 4, i.e., better than the British, German and Later US

torpedoes. I don’t understand the reason for this. The Italian

torpedoes were slightly faster, but had smaller warheads, than other

nations, and the French torpedoes were about average, so I have

downgraded both of them too.

The 5 to 4 reduction should mean that at about

66% of heavy cruisers, 50% of light cruisers, and 17% of the

destroyers survive being hit by Long Lances, albeit mostly as

"mission kills".

This

is not perfect, especially for the destroyers, but there is a limit

to what you can do with a D6 based system. I don’t think that I am

being too negative on the Long Lance here. Also, the addition of

non-broken back torpedo special effects enhances the effects of all

torpedoes and can also lead to the destruction of ships.

Rules tweaks notwithstanding, the most important takeaway from this

game is that two players controlled 27 ships, and manoeuvred and

fought them to a reasonably historical conclusion in an easy

afternoon’s play. Most other reasonably complex WWII naval rules

that I know of begin to creak and groan if a player has to command

more than four or five ships, and commanding double figures is

usually unthinkable, or it reduces the action to a snail’s pace as

plotting, calculating and recording take over from moving and

shooting as the main features of the game. This is a great tribute

to Nimitz’s original design. My amendments merely add some of the

factors that Mr. Mustafa left out in search of a really quick game.

So, if you are new to WWII naval wargaming, or if you have spent a

lifetime, man and boy, before the mast searching the seven seas for

a good set of rules, give Nimitz a go. If you want a fast and

furious fight use the RAW. If you want something more nuanced and,

if I say so myself, more historical, to challenge you, try the

Cunningham amendments, or any of them that you personally approve

of.

Above all, Nimitz is fun. Admiral Abe, whose

last memory was an almighty flash and bang as Hiei’s forward

magazine went up 50 feet in front of his face, was well enthused.

Never having played WWII naval before he left considering buying the

British and Italian fleets, and a new samurai sword to replace the

one that lies nine fathoms deep in Ironbottom Sound.

[1]

I have

no idea how deep the waters south-east of Savo Island are, The

line is stolen from the Ancient Mariner.

|