|

Our

Grandfathers' Wars

Part

IV: Triumph

and

Safe

Return

by

Peter Hunt

Having

tried, and failed, to break through to Ladysmith by his attacks on the Boer

lines west of Colenso, Buller attacked the Boer positions east on the town

on 12 February 1900.

Downstream

of the town the Tugela curves through a steep valley with high ground on

both sides of the river. The

Boers had approximately 3,000 men north of the river and 1,500 south of it.

Against these Buller could bring 28,000 men and 78 guns.

Despite their recent victories Boer morale was beginning to crack,

especially amongst the Orange Free Staters as news of Lord Roberts’

invasion of their homeland came through.

Also their commanders in the eastern sector, Lucas Meyer and

Christiaan Fourie were nowhere near Botha’s ability.

The British attack was relentless and well coordinated, whilst the

Boers made several elementary mistakes.

Within a week the hills south of the Tugela had been cleared and the

British artillery moved up to pound the Boer positions on the other side,

which were in a series of hills known as the

Tugela

Heights

.

The Tugela Heights

On

21st February 1900 the British crossed the river again.

The Boers had been reorganized by Botha and were well dug in and

concealed in the heights above them so progress was slow and bloody.

By the 23rd they had dented the Boer position by taking Wynne’s

Hill, (the British named the hills after their brigade commanders,) but not

cracked it. Wynne’s Hill was

fiercely contested by the Boers and the situation was beginning to look like

a re-run of Spion Kop. Wynne’s

Hill was dominated by Terrace Hill, which in turn was flanked by Railway

Hill and Pieter’s Hill. So,

Buller directed Hart’s Irish Brigade to take Terrace Hill, which

thereafter became known as “Hart’s Hill”.

Hart’s

reputation for reckless determination had spread throughout the army.

Churchill regarded him as “one

of the bravest officers in the army, and it was widely felt that such a

leader and such troops could carry the business through if success lay

within the scope of human efforts.” Conan-Doyle,

without disparaging the General himself, noted that he was a dangerous man

to be around, although this was taken in good, but grim, humour: “Whom

are you going to?” “General Hart,” said

the aide-de-camp. “Then

good-bye!” cried his fellows.” However

Conan-Doyle also believed that Hart’s treatment of his brigade had turned

them into experts at facing fire and storming positions.

He reported “a shrewd

military observer” as saying that the brigade’s “rushes

were the quickest, their rushes were the longest, and they stayed the

shortest time under cover.” In short, it was known that the assault on

Hart’s Hill would be difficult and dangerous, but, if any men in the

British Army could pull it off, it was men like SGT Barnett and his comrades

in the Irish Brigade who would do it.

The

Inniskillings led the brigade and started at 12:30 p.m.

Much of the approach march had to be made in single file and things

got worse when a stream had to be crossed over a bridge dominated by a Boer

‘pom-pom’, (a 2-lber., Maxim-Nordenfelt, belt fed artillery piece,)

which inflicted 60 casualties. So

it wasn’t until 5 p.m. that the Inniskillings and the regiments straggling

behind them were assembled at the bottom of the hill in an area of dead

ground that became known as ‘Hart’s Hollow’.

With less than half his brigade available and with night coming on

Hart, true to form, decided not to wait.

He ordered the hill to be taken within two hours.

As the Inniskillings set off up the slope 60 British guns fired on

the Boer position and Hart ordered his bugler to sound the “double” and

“charge” again and again to spur them on.

Boer

defenders

As

the brigade advanced they came under fire from the adjacent hills and

companies were told off to suppress this fire, leaving the brigade in an

“arrow head” formation with the Inniskillings being the point.

The bombardment, and the determination of the likes of SGT Barnett,

seemed to do the trick. The

Boers could be seen leaving their positions ~ this was to be no re-run of

Spion Kop. But then the truth

dawned . . . ‘Terrace Hill’ was aptly named because it is a series of

terraces and the position that the Inniskillings were assaulting was only

the Boer forward line. Their

main position, 300 metres further up the steep slope, was strongly held, and

untouched. The artillery fire

had lifted and, with the lack of communication, failing light and confusion

of the attack, could not be effectively brought down on the new position.

This was not a re-run of Spion Kop, it was a re-run of Taba Nyama.

George

Barnett’s commanding officer, Lt. Col. T.M.G. Thackeray, was renowned for

his personal bravery. At Colenso

he had been cut off by the Boers, surrounded and called upon to surrender.

He refused. The Boers

would not take him alive. However

the Boers saw no point in taking him dead and adding another brave man to

the butcher’s bill that day. They

had already won their battle so they let Thackeray go.

Now, two months later, as night was falling on Hart’s Hill,

Thackeray’s courage, in all senses, was tested again.

Perhaps a man with less personal courage would not have gone on.

Perhaps a man with more morale courage might have assessed the

situation in a more sanguine manner and refused to go on, accepting Hart’s

ire and the opprobrium of the army and even his own men.

But Thackeray was not such a man, and there was no ‘perhaps’

about his own attitude. So,

perhaps inevitably, he led his regiment forward.

From

a hill on the other side of the river Churchill had a grandstand view, and

probably a much better idea of what was really happening than either General

Hart, Colonel Thackeray or Sergeant Barnett did.

Churchill could see the Boers rise in their trenches to be able to

fire better, and described what happened next:

“The

terrible power of the Mauser rifle was displayed.

As the charging companies met the storm of bullets they were swept

away. Officers and men fell by

scores . . .It was a frantic scene of blood and fury . . . Thus confronted,

the Irish perished rather than retire. A

few men indeed ran back down the slope to the nearest cover, and there,

savagely turned to bay, but the greater part of the front line was shot

down.”

Companies

from other regiments of the brigade advanced to support the Inniskillings

but this just added to the slaughter. This

time the Boers did not give Thackeray a chance and he paid the ultimate

price. The Colonel of the Dublin

Fusiliers died on the same slope and the Colonel of the Welsh Fusiliers was

killed whilst leading a diversionary attack on their left.

Three colonels dead in one evening speaks volumes about the men who

led Sergeant Barnett and Private Hunt. If

they can be criticized for regarding their men as expendable parts in the

Empire’s war machine it must be accepted that they regarded themselves in

the same way ~ and they didn’t ask their men to do anything that they were

not prepared to do themselves.

What

was left of the Inniskillings and the rest of the brigade clung on to the

lower terrace throughout the night, and all through the day after too.

The next day a truce was called to remove the dead and wounded.

During the attacks of the 23rd out of 1,200 men engaged the Irish

Brigade had lost over half as casualties.

As well as being known as “Terrace Hill” or “Hart’s Hill”

the height would now be known as “Inniskilling Hill.” Today a simple

monument stands there which is inscribed:

“Near

this spot were killed, or mortally wounded on Feb 23rd – 24th 1900 Lient-Col

T.M.G. Thackeray, Commanding. Major.

F.A. Sanders, 2nd-in-command, Lient W.O. Stuart and 65 NCO and men of the

27th, Inniskillings whilst advancing to the relief of Ladysmith.”

After

days of continuous fighting, hopelessly outnumbered, and with nothing but

bad news from the

Orange Free State

, the morale of the Boers on the Tugela was at breaking point.

But, just like at Spion Kop and Valkrans, the British were pulling

back south of the River. On 26th

February Botha reported to Joubert that:

“It

is quite possible the enemy is retiring again.

Their wagons . . . tents . . . [and]

big guns have already recrossed the River . . . [s]ome

of [their infantry] have already

left. It is evident that their

losses are heavy. By tomorrow,

we shall know for certain what the enemy’s intention really is.”

Inside

Ladysmith the hunger, the war and the anxiety continued.

“It was the anxiety which

killed” said Jacson. “There

is nothing more conducive to the deterioration of men’s minds than false

alarms on an empty stomach.”

Although

Buller’s guns could be heard every day, and occasionally even seen hitting

the southernmost positions of the Boer siege ring, and although Boers could

be seen trekking north, this was not necessarily an indication of British

success to the south. Lord

Roberts was pushing into the

Orange Free State

and the Boer movements could just be re-deployments to meet this threat.

Unable to storm Ladysmith the Boers tried to flood it out by damming

the

Klip

River

. The British shelled the dam

and this sparked fierce artillery exchanges.

On 22nd February the Devons were ordered to probe the Boer siege

positions to see if they had been weakened.

An early morning attack found the Boers still in place and as

determined as ever.

On

25th February the garrison was put on full rations.

What a relief this must have been for Private Hunt and his fellow

rankers for, without money, they had no access to what remained of the

town’s commercial stocks where one egg would cost the equivalent of four

days of a private’s pay. Then,

on 28th February, the blow fell. Rations

were cut to their previous level: one biscuit, three ounces of mealies, and

one pound of horse per man per day.

“This,”

recorded Jacson, “was perhaps the

most distressing circumstance connected with the siege, and it had a most

distressing effect. It was not

so much the reduction of the ration that was of consequence as the reason .

. . that Buller had again failed, and could not get through.” With

no news from Buller, General White had calculated that on the reduced,

starvation rations the garrison could eke out another fortnight, by which

time there would not be a horse, ox or mule left.

Sir George White was giving Sir Redvers Buller his last chance.

This

time both Botha and White were wrong. The

sacrifices on Wynne’s Hill and Hart’s Hill were not to count for nothing

as the sacrifices at Colenso, Taba Nyama, Spion Kop and Valkrans had.

Buller was moving his big guns south of the river so that he could

concentrate them on the fourth hill of the

Tugela

Heights

position, which was known as Pieters Hill, and, from 27th February 1900, as

‘Barton’s Hill’, after the British brigade commander who took it under

a massive artillery bombardment. This

attack unhinged the Boer positions on Railway Hill and Hart’s Hill.

SGT Barnett and his comrades in the Inniskillings, indeed in the

whole army, could move forward again. The

way to Ladysmith was open.

At

6:30 p.m. on 28th February, whilst Private Hunt was probably listening to

his tummy rumbling, a mounted column was seen in the distance to the south

of Ladysmith. Nothing unusual

here, the Boers had been moving for days.

But then it was realised that this column was riding in formation and

Boers didn’t ride like that . . . the column must be British: Ladysmith

had been relieved!

On

3rd March Buller’s army marched in review through Ladysmith.

“A pagent,” said Jacson,

“which those who took part in the

siege will never forget.” The

Devons were given pride of place outside the town hall, next to Sir George

White. Buller and his army “received

an immense ovation [from] the

lines of the weedy, sickly-looking garrison.

These with their thin, pale faces cheered to the full bent of their

power.”

Ladysmith

Town Hall. Private Hunt sat outside whilst Sgt Barnett marched past

Buller,

showing his usual consideration for the men, bade the exhausted defenders

sit whilst the relievers marched past. Jacson

described SGT Barnett and his comrades as:

“these

men . . . to the weakly garrison appeared as veritable giants . . . They

were . . . well covered, hard and well set up.

They were filthy, their clothes were mended and patched, and most of

them had scrubby beards . . . But how well they looked – the picture of

vigour, health and strength, as they “tramp, tramp” – “tramp,

tramp” through town.”

So

Sergeant George Barnett and Private George Hunt had probably come

face-to-face that day. Although

they did not know each other, (and couldn’t possibly have known, or

comprehended, that a century later their descendents would come to know each

other through something called ‘the Internet’) I am prepared to bet that

they were both very pleased to see each other.

Ireland Ward

The

word ‘probably’ is used advisably because, as you can see from the faded

photograph above, at some point in South Africa George Barnett was

hospitalised. When, where and

why, from a wound or disease, we do not know.

All we can say is that, given what the Inniskillings had been through

between Colenso and

Tugela

Heights

, it is more likely that SGT Barnett was hospitalised at this time rather

than later. Take a close look at

the picture and you will get a clue why the two Georges could survive the

hard times they went through: George Barnett is in ‘Ireland Ward’, which

indicates that even in hospital the ‘regimental’ system was maintained

as far as possible. Private Hunt

and Sergeant Barnett fought harder, better and longer because they did so

alongside their pals in the regiment, and even when injured they were kept

amongst their pals where the common experience and mutual understanding and

support would result in a better and quicker recovery.

Happily

whatever put SGT Barnett in hospital it was not a permanent disability and

for George Barnett, and George Hunt, the war continued.

The Inniskillings and the main body of Buller’s army moved north to

liberate the rest of

Natal

and to take the war into the Boer homelands. Meanwhile the Devons were

placed under the Command of Brigadier Walter Kitchener, (Lord Kitchener of

Khartoum

’s brother) and given ‘line of communication’ duties so that they

could recover from the debilitating effects of the siege.

Even these duties were no soft option.

Having been starved for so long the men ate too much and suffered

from jaundice; and, still clothed in their Indian summer kit, were not

equipped to face the austral winter on the high veldt.

This was no mere inconvenience, for instance on the night of 9th

August 1900 two men from the Devons’ sister battalion, the Rifle Brigade,

died of exposure in sub-zero temperatures.

Lord

Roberts’ army cleared the

Orange Free State

and met up with Buller’s army from

Natal

outside the Transvaal capital of

Pretoria

. What was left of the Boer

armies fell back along the railway line towards

Mozambique

with Lord Roberts, General Buller, Sergeant Barnett and Private Hunt all in

hot pursuit. The Boers made their last major stand on the hills between

Belfast

and Machadodorp on 27th August 1900. The

key to their position was the Bergendal Kopje held by the Johannesburg

Police. The British brigades had

become intermingled during the pursuit and

Kitchener

took over temporary command of the Inniskillings.

These, along with the Rifle Brigade, led the assault, with one

company of Devons directly attached to the leading company of Inniskillings

and the rest of the Devons in close support.

Both Georges have medal bars for this battle, they were truly

‘brothers in arms’ that day.

For

three hours the British brought 39 guns to bear on the Boer position which

measured only 80 yards by 40 yards. So

intense was the bombardment that the hill was stained yellow by the

chemicals from the Lydite shells. Unlike

the situation at Hart’s Hill the artillery kept up the fire until the

assault lines were almost on top of the Boer sangars.

The Boers fought with their usual tenacity, Conan-Doyle says the

Jo’ Burg Coppers “may have been

bullies in peace, but were certainly heroes in war . . . No finer defence

was made in the war” and they punished the Rifle Brigade badly.

But companies A and B of the Inniskilling Fusiliers were the first

into the Boer position and as a result of this penetration the whole Boer

line fell back, although still in good order.

In

the hills beyond Machadodorp men like George Hunt and George Barnett were in

their element. Accounts of the

pursuit read more like the North West Frontier than

South Africa

. The mountains were steep,

(over 8,000 feet high,) the valleys deep, but there was always a way through

or around for men who knew their mountain warfare.

The Devons and the Inniskillings had studied in a hard school under

the wily Pathans and they had learned their lessons well.

Organised Boer resistance finally ended when, on 26th September 1900,

the Devons stormed the aptly named Burgher’s Nek.

Two days earlier British cavalry had reached the

Mozambique

border at Komatipoort. President

Kruger had fled through here a week before.

The war appeared over.

The

previously indomitable Botha summed it up thus:

“I

shall give it up. I have taken

up position after position which I considered impregnable; I have always

been turned off by your infantry, who come along in great lines in their

dirty clothes with bags on their backs.

Nothing can stop them. I

shall give it up.”

At

Spion Kop it had been Botha, and the Boer will, which had triumphed over the

British will. But it had been

the will of unstoppable men like Sergeant Barnett and Private Hunt, in their

dirty clothes with bags on their backs, that had eventually triumphed.

But,

alas for the British, although the Boer armies had been broken in the field

the Boer will to resist had not been broken.

The war now entered its guerilla stage as Boer Commandos under men

like Fourie, De Wet, Erasmus, De la Ray and others took the war to the

British lines of communication, to show the British that they might have

conquered the Boer territory but they had not conquered the Boers.

The

guerilla war can be roughly divided into two stages.

For the first eight months or so the Boer commandos tended to be

larger groupings, often with families and cattle on the hoof accompanying

them. These at least gave the

British a target for formal operations against them.

Large ‘sweeps’ were mounted to pin down the Boer laagers.

Jacson tells of the Devons performing 20 mile night marches over

difficult ground to attack Boer laagers at dawn.

It was in one of these sweeps in May 1901 that Private Hunt did

something wrong and lost his good conduct pay for a year as a result.

His service record is silent on the actual offence and I have often

wondered what it was. The fact

that he was not a clockwork paragon of military discipline makes me like the

Grandfather I never knew even more.

The

Devons were mostly deployed in the eastern Transvaal whilst the

Inniskillings went further afield, to the western Transvaal and

Cape

Colony

as well. The Devons were the

luckier regiment for they shipped out of Africa, bound for India again, on

January 3rd 1902 and thus missed the worst part of the guerilla war against

the Boer ‘bitter-enders’. This

constituted the second stage of the guerilla war with the Boers breaking

down into smaller groupings of combatants only, highly mobile and living off

the land by way of what they could gather from their supporters or pillage

from their opponents. Against

these highly mobile groups even infantry which could make 20 mile night

marches were not much use, and the Inniskillings found themselves manning

some of the thousands of blockhouses that were erected to protect the

British lines of communication, a thankless, tedious and dangerous task with

the monotony of endless guard duty occasionally relieved by the terror of a

Boer attack. Sergeant Barnett

and his platoon spent the last three months of the war in the blockhouse

line around Kaffir Kop. Their

feelings when peace was finally declared on 31st May 1902 can only be

imagined.

The

two George’s paths probably did not cross after Machadodorp.

Private Hunt and the Devons left

South Africa

early with their reputation enhanced. Their

general, Walter Kitchener said of them:

“a

more determined crew I never wish to see, and a better regiment to back his

orders a General can never hope to have.”

But

even this high praise was not enough to keep my Grandfather in the army.

He had seen enough soldiering and took his discharge in January 1904

with 12 years and 70 days of service.

George

Barnett with the band

For

George Barnett however the army was his life.

He continued to rise through the ranks, transferred to Jersey Militia

in 1903, represented his regiment at shooting at Bisley, (perhaps he had

learned a thing or two about sniping from the Pathans and the Boers,) and,

as Regimental Sergeant Major spent his last years in service training the

recruits for a new war that was to end all wars.

I can think of no better type of man to prepare younger men for the

horrors of the Western Front than one, like George Barnett, who had been

through the horrors of Colenso, Taba Nyama and Inniskilling Hill and lived

to tell of it, and to learn from it. When

he retired with 30 years’ service in 1917 the local paper noted that

Regimental Sergeant Major Barnett was “popular

with all ranks, he is a veritable type of British soldier of the old army .

. .”.

The old army that George Hunt and George Barnett represented died at

Ypres

. The great wars of the 20th

Century would be fought mainly by short service volunteers and conscripts,

not by long service men. Oddly

enough, the Pathans and Boers probably had more in common with the new

soldiers of the 20th Century than they had with the old soldiers of the 19th

Century. They too were part time

citizen soldiers, who fought on the offensive because they believed they had

a cause, and on the defensive for their hearths and homes.

On the other side Private Hunt, Sergeant Barnett, Captain Jacson and

Colonels

Park

and Thackeray fought because that is what they did, as soldiers of the

Queen. This was summed up on

Sunday, 25th February, 1900 during the truce to remove the dead and wounded

after the slaughter on Inniskilling Hill, when British officers fraternized

with Boer farmers. Over shared

tobacco the Boers made it clear that they would rather be back on their

farms but would stick out the war for however long it took.

The Boers could not understand how the British could accept such

heavy casualties, and suggested to a British Major-General that the British

were having a rough time.

“A

rough time?” Replied the British soldier. “Yes

I suppose so. But for us, of

course, it is nothing. We are

used to it, and we are well paid for it.”

[Private Hunt received one shilling and three pence a day before

stoppages!]

“This is the life we lead always, you understand?”

The

Boers looked at the British dead around them and realized the type of men

they were up against . . . “Great

God!” they said.

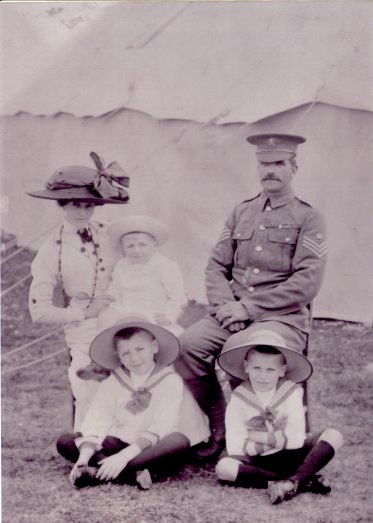

George

Barnett and family

back

to the contents page back

to colonial wars

|