|

VISITING

A GRAND OLD LADY

A

Voyage Around HIJMS Mikasa

by

Peter

Hunt

Who

is She?

The

Mikasa holds the same historical, and even cultural, significance for the

Japanese as HMS Victory does for the British.

Likewise her famous admiral, Heihachiro Togo, holds a similar place in

Japan

’s pantheon of heroes as Horatio Nelson holds in Britain’s. All represent the finest

hour of their countries’ naval traditions.

Everything in their naval traditions before the climatic battles of

Tsushima

and Trafalgar was leading up to those points.

Everything in their naval traditions afterwards looked back to those

points for inspiration.

|

|

|

Togo and the Mikasa. |

After

their defeat of China in 1895 the Japanese felt robbed of the spoils of

their victory by the coercion of Russia, France and Germany which led to the

Russians being ceded the Liaotung Peninsula, and trading and military rights

in Manchuria and Korea, which the Japanese saw as theirs alone.

To ensure that they would never again have to back down from the mere

threat of force, the Japanese decided upon a major increase in their fleet.

The resulting “6+6” programme was intended to furnish six battleships

and six armoured cruisers in ten years.

The ships of the programme, (plus two more Italian built armoured

cruisers purchased from

Argentina,) made up the main Japanese naval force in the war with

Russia

which started in February 1904. The

Mikasa was the last of the six battleships built under the programme.

Mikasa

was ordered from Vickers and Sons in Britain in 1898, she was launched in November 1900 and was completed, and became

flagship of the Japanese fleet, in 1902.

In size and power she was a close cousin of the British Formidable

class battleships and, as such, represented the penultimate step in

battleship development before she, and all her sisters, were made obsolete

by the launching of HMS Dreadnought. But,

for her day, she was one of the most powerful ships afloat, displacing

15,140 tons, armed with four 12” guns, 14 6” guns, 20 12 pounder (3”)

guns and four torpedo tubes. She

was protected by nine inches of Krupp cemented armour and the 15,000

horsepower of her reciprocating engines drove her at 18 knots.

In DBSA terms she is the archetypal First Class Battleship.

One

thing that the Mikasa wasn’t was what Royal Navy matelotes would term a

“lucky ship” ~ a ship which survives unscathed through the thick of the

action. Mikasa saw four wars but

the price of her fame came high in the blood of her crew.

She was also more than usually unfortunate when out of combat as

well.

As

Togo’s flagship from the beginning of the Russo-Japanese War, Mikasa took part

in the blockade and actions outside Port Arthur. When the Russian fleet

attempted a break-out in August 1904

Togo

intercepted them in the

Yellow Sea. In the ensuing battle it

seemed at first as if honours on both sides were roughly equal, with the

Japanese, if anything, on the losing end of the exchange.

The Mikasa herself was very badly mauled; her after turret was

knocked out and she took 20 hits. 125 of her 860 man crew were casualties.

However, just as it seemed that the Russians might be able to break

off at dusk and succeed in getting through to Vladivostok a shell from the

Mikasa hit the Russian flagship’s bridge and conning tower, killing the

Russian admiral and causing the flagship to circle out of control, followed

by some of the other Russian ships. By

the time that order was restored in the Russian fleet, the chance of escape

had been lost and they were driven back into Port Arthur

.

The

Russian fleet was only to be eventually destroyed months later as the 11”

howitzers of the Japanese Army picked off the ships inside Port Arthur, whilst Mikasa and the rest of the fleet maintained the blockade outside.

After a much needed refit Mikasa and the rest of the fleet made ready to

meet the new enemy; the Russian Second and Third Pacific Squadrons, in

effect the Baltic Fleet, which had made an epic eight month voyage around

Africa to the

Sea of Japan.

|

|

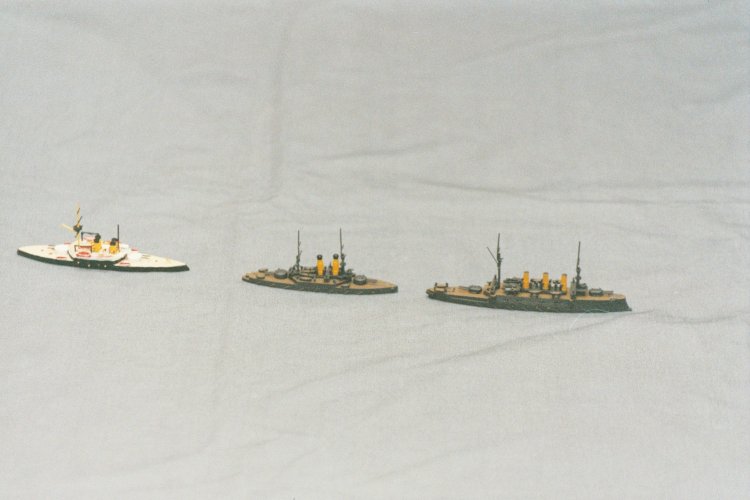

Some of the Russians

at Tsushima. Oslyabia followed by Sissoi and Navarin.

Models by Konishi and scratchbuilt. |

At

1339 hrs on May 27th, 1905 in the straits of

Tsushima

the Mikasa leading the Japanese line sighted the Russian fleet at 13,000

metres.

Togo

was on the starboard bow of the Russians.

If he turned to port he would engage them in a classic fight on

reciprocal courses, this would eventually bring all of his ships under all

the guns of the Russian fleet. If

Togo

turned to starboard he would have to slow down to engage the front of the

Russian line with his whole fleet thus giving the Russian the initiative of

manoeuvre. Instead of these two

weak options Togo

took a calculated risk, crossing the Russian “T” outside of gunnery

range and, as the Russians opened fire, he then turned his line through 180

degrees. This brought him on a

parallel course with the Russians where he could use his speed advantage to

concentrate on the separate parts of the Russian fleet at will.

|

| Mikasa and

her consorts. Models by Navis. |

At

Trafalgar, 100 years before

Tsushima, Nelson had made a high risk approach in order to achieve a decisive

advantage to reap decisive results. Like

the Victory the Mikasa bore the brunt of the enemy fire whilst the decisive

manoeuvre was taking place and she was hit 25 times in the first 30 minutes

of the battle. And, like the

Victory flying Nelson’s “England Expects”, Mikasa was flying Togo’s “Z Flag” signal: “The

fate of the Empire depends upon this battle.

Let every man do his utmost.”

The

danger of “Togo’s turn” was that whilst making it, most of the Japanese

fleet would be masked, whereas the Russian fire would be enhanced because

they could fire on a fixed point ~ the knuckle of the turn ~ to which they

already know the range, as each Japanese ship passed through this point.

Like Nelson, Togo had taken a finely balanced risk ~ but his judgement

had been right, and although the Mikasa was badly battered, and one of his

armoured cruisers was knocked out, the Japanese line shook itself out,

returned the fire from a tactically advantageous position and from then on

fought the battle on its own terms. By

the next morning almost the entire Russian fleet was either sunk,

surrendered or in flight for neutral ports ~ only three of the thirty-eight

Russian ships made it to Vladivostok. The

war was, to all effects, over. To

pay for this decisive victory Mikasa was hit 32 times and 113 of her crew

were casualties.

After

all this sacrifice Mikasa was deserving of a safe peace, but it was not to

be. In September 1905, in Sasebo

Harbour, unstable shells in her after magazine ignited, the fire lead to explosions

and Mikasa sunk, taking 339 of her crew with her.

She was raised in August 1906, rebuilt and became fleet flagship

again in 1908. Although she was

active throughout World War One, with the commissioning of Japan’s dreadnoughts, naval technology overcame her.

Mikasa was quickly

relegated to second class, third class, and finally coast defence status.

In this role she suffered the ignominy of running aground off the

Russian coast during the Japanese intervention in the Russian Civil War in

1921. Returning home Mikasa was

holed and flooded during the Great Kanto Earthquake of September 1923.

In

1925 it was decided to preserve Mikasa as a memorial ship and she was

encased in concrete in her home port

of Yokosuka. Even in this state she was not

safe and was extensively bombed during World War Two.

After the war the American occupation authorities confiscated the

Mikasa and ordered her scrapping, but this was low on the priorities in post

war Japan. Then times changed.

The Cold

War started and the Mikasa, which could have been seen as a very potent

symbol of Japanese militarism, was seen as a potent symbol of national unity

against the old enemy who had become the new enemy ~

Russia. Instead of being scrapped the

Mikasa was restored for the second time and re-inaugurated in 1961.

Since then the Mikasa hasn’t been shot at, blown up, run aground or

damaged in earthquakes. Long may

it remain so.

Where

is She?

On

the shore of Shirahama

Bay, Yokosuka, South of Tokyo.

To

get there from

Tokyo

take the Yamanote subway line, which circles most of the tourist areas of Tokyo

to Shinagawa, the fare will be about 200 – 230 yen.

Then change to the Keihin Kyuko line for

Yokohama, Yokosuka

and points south. The fare is

620 yen and the trip to Yokosuka Chuo Station will take about 35 minutes if

you catch one of the limited stop expresses, which are marked with red and

green numbers, or more than twice that if you take the country train which

stops at every station ~ guess which train I caught on the way out?

From Yokasuka Chuo Station it is a five minute walk to the seafront.

The official website is at: http://www.kinenkan-mikasa.or.jp/

although there is little in English. There is further information at: http://www.city.yokosuka.kanagawa.jp/mikasa/gide.html.

What

is She Like Now?

Well

firstly, I hope that I look as good when I am 106!

The

really interesting thing that struck me about treading the decks of a

pre-dreadnought is that the “pre” is really brought home to you.

Compared with other preserved ships that I have visited Mikasa still

seems to have more in common with the Victory, Constitution and Warrior than

with the Texas and Belfast. I’ll

explain this feeling as we take a trip around.

As

you go through the gates you are greeted by a statue of Togo, standing proudly before his flagship.

As a lad

Togo

had served in the shore batteries at Kagoshima

in 1862 when the British Royal Navy had shelled the town and shown up the

dying Shogunate as the weak and antiquated power it was.

Learning from this humiliation, under the Meji Restoration and the

modernization of

Japan, Togo

had become a prime example of the new paradigm: “imitate and overtake.”

Whilst the Japanese Army was modelled first on the French army, then

on the Prussian, the Japanese Navy held a true course in the wake of the

Royal Navy…relying greatly on British shipbuilding, British methods, and

even adopting British naval ethics. Like

the British commanders of the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, Togo was not

concerned about diplomatic niceties when it came to getting the job done.

In July 1894 he had started the Sino-Japanese War by shooting first

rather than let the Chinese get an advantage.

He also had no qualms about sinking neutral British merchantmen in

the service of China. Likewise, in 1904 he attacked

the Russians in Port Arthur

before the formality of a declaration of war.

Togo

was a hard man, always focused on his goal.

As such he was not an easy man to work for.

He seems to have been universally respected and admired by his fleet,

but those who worked closely with him found it hard to love him.

He was particularly difficult in the days running up to Tsushima

because he knew that if the Russian fleet, which had three possible routes

to Vladivostok, slipped past him, the successful outcome of the land war,

which had nearly bankrupted Japan in terms of both manpower and gold, could

be reversed. Finally news came

that the Russian support ships had docked at

Shanghai

and from this Togo

knew that the Baltic Fleet must be heading straight for him rather than

taking the two other possible routes out into the Pacific.

With his strategic judgement proved correct

Togo

could relax a bit ~ all he had to do now was to find and destroy the

Russians, and he never had any doubts he could do that.

|

|

| The bronze

plaque marking Togo's station ~ on top of the pilot house. |

The

statue is based on the famous picture of

Togo

of the flag

bridge

of

Mikasa

at Tsushima. Since the picture was painted

whilst all the participants were still alive there is no reason to believe

that it was not an authentic representation.

This brings us back to the “Pre” thing.

Look at Togo. He is in a

20th century uniform but when he leads his fleet into battle he still wears a

sword, just as admirals would have done a hundred years before, but would

never do again.

Although

Mikasa is encased in concrete up to the waterline this does have one

advantage over most memorial ships which are either dry docked or still

afloat ~ you can get much closer to her.

The affect is only spoiled by a fibre-glass cabin on the port beam

which houses, I think, the electrical transformers.

I’m sure that for technical and safety reasons this white box is

necessary but it does detract from the epic sweep of a 100 year old

broadside.

Entry

is a reasonable 500 yen and for this you get a couple of English guide

pamphlets too. Another 500 yen

will get you the 34 page English guide book.

Once on board your tour can conveniently be divided into two parts ~

above deck and below.

|

| The business

end. Note the sighting hoods on top of the 12" turret and

conning tower under the pilot house behind. |

Starting

above deck, and at the business end, the first thing that struck me was the

prominence of the sighting hoods on the 12” gun turrets fore and aft.

In the days before director control the approximate range to the

target was passed down from a small range finder on roof of the pilot house

to the gun captain in these armoured pimples, and direction given to the

turret crew below. When a gun

was fired a ship’s boy or midshipman would start a special stopwatch

calibrated not in seconds but in metres, with the hand moving at the same

rate as a shell would fly. So if

the range to the target was estimated at, say, 4,000 meters, when the hand

reached 4,000 the boy would shout “splash.”

The gunnery officer in the sighting hood could then judge from the

real splash or hit he saw whether the range estimation was over or under

and, hopefully, could tell the difference between his own splashes and those

of other guns firing at the same target.

|

|

|

The inside of the

conning tower. |

The

bridgework is a mixture of the old and new in naval warfare.

The armoured conning tower was “state of the art” protection.

Inside the captain, navigating officer and helmsmen would be safe,

even from most direct hits, unless a splinter entered through one of the

narrow vision slits. If shrapnel

or splinters did get in, with any momentum behind them, the results were

devastating as they would rattle around, bouncing off the equally heavily

armoured inside of the tower into the closely packed sailors inside.

Outside of the conning tower on the disengaged side would have been

another midshipman using a sextant to measure the angle to the masthead of

the ship ahead and thus give the captain the separation distance so that the

squadron could maintain proper station.

Exactly the same method was used in Nelson’s day.

Above

the conning tower was the bridge proper, with the wheelhouse and chart room.

On the exposed roof of this stood Admiral Togo

with his staff officers, orderlies and signallers, a battle staff of 12 to

control the fleet. Although this

position was “protected” from splinters by rolled hammocks these were no

use against 12” shells, so Togo

was every bit as vulnerable as Nelson on his quarterdeck.

The alternative was to command from the already crowded conning tower

with poor visibility and poor signalling options.

The British Naval Attaché, Captain Jackson, records that six of the

other seven Japanese admirals at Tsushima followed Togo’s lead, operating from on top of the pilot house, thus sacrificing

personal safety for better command and control.

Given that most of the ships’ crews would have been behind armour

we thus have the very rare military situation where the high command was at

much greater risk than most of the men they were sending into battle.

At the battle of the Yellow Sea a Russian shell took away four of Togo’s staff.

|

| The 12

pounder battery. |

The

12 pounder battery on the upper deck on either side of the funnels is

another place that Nelson would have felt at home ~ an open gun-deck with

guns firing out through ports on the broadside.

In action though it would have been a lot more cluttered than it is

today. Between each gun was a

hemp rope mantelet, a sort of thick climbing net, that was supposed to stop

splinters. The naval historian

D. K. Brown records that British tests in 1893 had shown such mantelets to be

“almost useless.” I hope

that for the peace of mind of Mikasa’s gunners no one told them about the

British tests. Another of

Britain

’s naval attaches to Togo’s fleet, Captain Troubridge, recorded that in one of Mikasa’s sisters,

behind the rear of the guns, was placed a protective barricade consisting of

a pile of gear about six feet high and four feet thick covered with wetted

canvas. This gear sometimes

consisted of “bags of vegetables, principally the vegetable like a long

turnip, so much eaten in Japan.” In a rare omission, in his

otherwise detailed and well written books, D. K. Brown does not record the

results of any British tests on the resistance value of Japanese turnips.

|

|

|

The rope mantelet. |

Before

you go below check out the radio room in the aft superstructure.

Radio telegraphy was in its infancy when Mikasa was built but the

Russo-Japanese War proved its utility. Whilst

Nelson had to guess where Villeneuve was, Togo

was informed over this radio by his scouts that the Russians were in Square

203. This gave a fillip to his

fleet’s morale as Hill 203 had been the key to Port Arthur’s defences, so it was an auspicious number.

Below

decks very little remains of the old Mikasa.

The 6” gun casements have been rather simply restored and some are

used as galleries. The wardroom,

officer’s cabins, (including, because this is a Japanese ship, a splendid

bath) and Togo’s quarters at the stern are still there.

But most of the main deck has been converted into an auditorium and

into exhibition galleries about the ship, the admiral, the war, and about

the Japanese Navy in general.

|

|

The automated wargame

table. |

If

you like ship models then this is the place for you.

Personally I would have preferred to see the preserved mighty

reciprocating engines like those on the Warrior or the Texas,

rather than a museum, but my slight disappointment was dispelled when I

discovered that the museum has a wargames table with the Battle of Tsushima

set up on it. And it’s the

sort of wargames table we have all always wanted too ~ an automated one!

On a simulated sea the two fleets sail from one end to the other on a

sort of chain mechanism. OK,

when I first saw that the ships were generic types of about 1:1800 scale and

not accurate individual models I was a bit put out, but when little lights

started flashing in the models when the ships fired, and when little water

spouts started rising out of the plasticine sea as the shells fell over and

short, my inner child was totally sold.

Needless to say I pressed the “start” button several times …

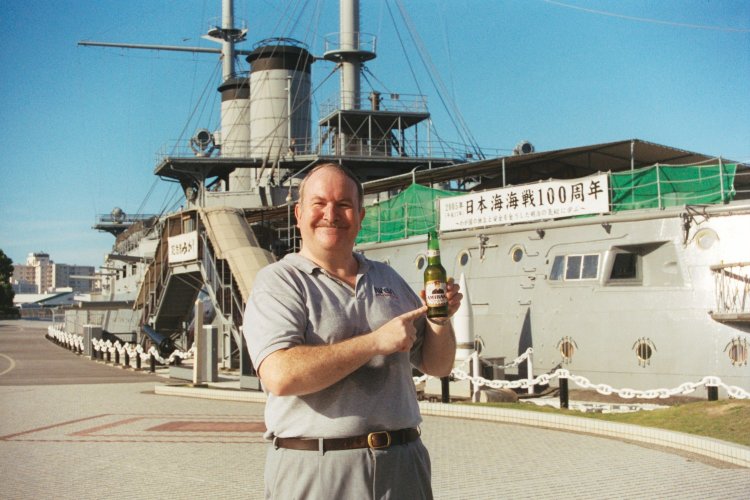

Before

you leave the site check out the gift shop for the compulsory T shirt,

prints, ship models and, to celebrate a visit to a fine old lady in the

proper spirit, a bottle of ice cold “Amiral” beer.

With a picture of Togo

on the bottle it is the perfect brew with which to toast the hero, and the

heroine, of battles a hundred years ago.

|

| The author

with a bottle of Amiral beer! |

back to

other

periods or

back

to expeditions

|