|

Our

Grandfathers' Wars

or

By

George!

Parallel Lives in the

British

Army a Hundred Years Ago

Part

III: Early Days and Darkest

Hours

by

Peter Hunt

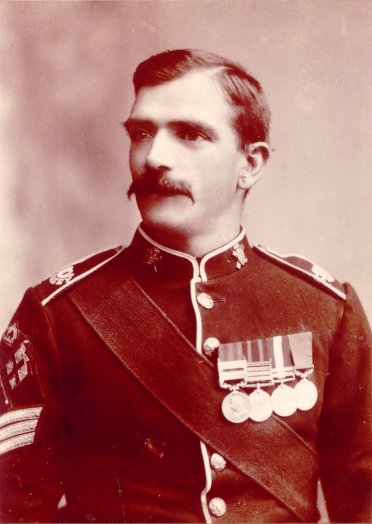

George

Barnett

He

wears the Queen's India Medal, The Queen's and the King's South Africa

Medals

and

the Long Service and Good Conduct Medals

It

is always reassuring to receive feedback on the articles in Despatches.

Knowing that

someone, somewhere in cyberspace, is actually reading this stuff is a reward

in itself. Since I wrote Parts I

and II of this series I had done some more work on my Grandfather’s

military life and had visited the South African battlefields in 2000.

I was thinking about going into print again, when I received a nice

email from Mrs Sheelagh le Cocq of Jersey, the

Channel Islands. Like me, Mrs le Cocq never knew

her grandfather but she had researched his life through family histories and

newspapers. Like my grandfather,

his name was also George and the two men had the same medal groups for their

military service, although Mrs le Cocq’s grandfather George Barnett served

in the Royal Inniskilling (although the town is Enniskillen) Fusiliers,

whilst mine, George Hunt, served in the Devons.

In Part II I related how George Hunt had been besieged in Ladysmith.

George Barnett was one of the men trying to relieve Ladysmith.

Both Georges then went on to fight the Boers on their own ground.

Although neither Mrs le Cocq nor I have any evidence that the two

Georges ever met it is clear that their paths crossed several times.

This, as they say, is their story . . .

For

a well spent 25 pounds sterling in 1997 I had a researcher get me copies of

my Grandfather’s service record and the

Devon

’s medal rolls. These filled

in many of the gaps in my knowledge of him, telling me where he was born,

what he did before he joined the army, and where and when he served.

Oddly enough on not one of the forms is his birthday recorded.

Clearly the army had no intention of throwing him a little party once

a year. But, since George H was

listed as 19 years and 10 months old when he signed up in November 1891, that

means he was born in January 1872, in the

village

of

Northam, Devon. George B was born three months

later in Islington, London.

Whilst

George Hunt lived with his father, became a groom and also served in the

part-time Militia until he joined the Devons when he was nearly 20, George

Barnett had a much rougher start to life. Mrs le Cocq suspects that George

may have been born out of wedlock because his father is described as a

“bachelor” in a later marriage certificate. No doubt, since he rose to

be a Senior NCO in the British Army, some of the privates that he was

responsible for keeping in discipline would have thought that this

background was an essential prerequisite for the job! George’s mother died

when he was very young and his father took a new wife who George didn’t

get on with. George later claimed that he had joined the army to escape a

“wicked stepmother,” but Mrs le Cocq charitably points out that the poor

lady had seven children in as many years, one of whom had died, and raising

this brood on a cab driver’s pay would have left Mrs Barnett harassed and

exhausted. When he was 11 George was sent to the Middlesex

Industrial

School, for continually running away from home. The Industrial Schools were

intended for unruly, but not delinquent or criminal boys, and most lads from

these schools entered the army. Mrs le Cocq doubts if they had much choice.

So, at the age of 14 years and 11 months in 1887, young George Barnett

signed on with the 2nd Battalion Inniskillings at

Aldershot, committing himself to 12 years’ service. It is an interesting insight

into the physical condition of working class boys in Victorian London that

George’s medical record shows the nearly 15 year old to have been 4feet, 6

½ inches tall and weighed only 77 pounds.

A

Victorian Band Boy similar to George Barnett

At

his age George Barnett would have been a band boy, playing the bugle, drums

and, because this was an Irish Regiment, especially the fife.

We know that George could play the trombone before he entered the

army so it is highly probable that he was in the Regiment’s band when they

marched past Queen Victoria

at her Jubilee Review in July 1887. This

was the easy sort of soldiering that Kipling alluded to when he wrote:

“You

may talk o’ gin and beer

when

you’re quartered safe out ’ere,

An’ you’re sent to penny-fights an’

Aldershot

it,”

but

by the end of the following year George was on a troopship bound for India

where he would have plenty of opportunity to practice the band boys’

secondary duty ~ they were stretcher bearers.

On

a personal note I thought that the Orient was amazing when I arrived in

Hong Kong

at the ripe old age of 22. You

really have to wonder what the 16-year-old George Barnett thought of it all

when he stepped ashore in Bombay in January 1889. He probably

didn’t have much time to think. The

battalion quickly moved to its station at Secunderabad and, after nearly

three years there, moved on to the even more exotic Burma where it spent the next four years. By

this time Private George Hunt of the Devons was catching up.

He arrived in

India

in December 1892, two months after his namesake had moved to Burma. By this time George Barnett

would also have become a fully-fledged infantryman.

The

two George’s first campaign together came in 1897 in the Tirah, which is

related in Part I of this series. The

Devons were in the main assault force under General Lockhart, whilst the

Inniskillings covered the flanks as part of the “Peshawar Mobile

Column,” based on Fort Bara. Here, according to their historian, they longed

“to be more actively

employed than in the necessary but uninteresting duties of road making and

fortifying the camp.” Their chance came when Lockhart’s regiments

withdrew and the Peshawar Column had to advance to save the hard-pressed rearguard.

This operation was a classic example of mountain warfare. The

Inniskillings and their sister battalions from the Peshawar Column entered

the hills and, passing through each other in succession secured the heights

for the rearguard to pass through to safety.

After being pursued by fanatic Afridis for five days and nights the

Scots, Sikhs and Gurkhas of the rearguard must have been rather pleased to

see the Irishmen, and Londoners, of the Inniskillings.

The interesting thing of course is that probably none of the English,

Irish, Scottish, Indian or Nepali brothers-in-arms who bivouacked at Barkai

on 14th December 1897 gave a moment’s thought to what an

amazingly diverse, but perhaps wonderful, Imperial army they composed.

George

Hunt’s enlistment papers are full of small print.

Whilst, theoretically, he signed on for seven years active duty,

“with the colours”, and five in the reserve, the sub-clauses provided

that, if the active service was overseas it could be extended by one year.

And if a state of war existed then, by yet another year.

And if “by a proclamation from Her Majesty in case of imminent

national danger” then all the service could be active, and it could be

extended for yet another year! My

Grandfather fell foul of every one of these clauses.

In December 1898 he was overseas in

India

and in December 1899 definitely at war in

South Africa. I don’t know if this

bothered him unduly, but as an old soldier he had a right to grumble and

I’m sure his contractual obligations gave him lots to grumble about.

George Barnett probably wasn’t grumbling about conditions of

service. At some point he had

decided that the Army was the life for him.

He had signed on again and by 1899 had been promoted to Sergeant.

A

private in marching order on the NW Frontier.

The

Devons wore the same kit in South Africa.

The

Devons and George Hunt arrived in South Africa on 21st September 1899 and in Part II I have related how they

soon found themselves besieged in Ladysmith.

George Barnett had been back in England

on leave when war broke out. He

was drafted into the 1st Battalion Inniskillings and arrived in Cape Town

on 30th November 1899 as part of Buller’s Army Corps which was

charged with breaking the Boer line on the Tugela River

and relieving Ladysmith, and my Grandfather.

Buller’s

first attempt at breaking through was at the Battle of Colenso on 15th

December 1899. The Boers, 4,500

strong under probably their best commander, Louis Botha, were dug in on the

north bank of the Tugela. Unfortunately

for the British, Buller had no real idea where they were.

His maps were wrong and this had not been revealed by careful

reconnaissance. Buller had

15,000 men in five brigades. Two,

(which included the 2nd Battalion of the Devons, trying to

relieve their 1st Battalion in Ladysmith) were to remain in reserve, one

was to attack on the right and one was to make a frontal attack on the

bridge across the river. The

other, the Irish Brigade under the command of Major General Arthur Fitzroy

Hart, including the Inniskillings, was the left prong of the attack.

Hart was ordered to cross the Tugela where it made a 300-degree loop

at “Bridle Drift [ford], immediately west of the junction of Doornkoop

Spruit [stream], and the Tugela.”

The

maps showed the junction to be upstream of the loop whereas in reality it

was downstream of it. Thus the

British thought that they would be crossing a drift at the outside of the 7

o’clock position on the loop when the drift they really wanted was at the

inside of the 4 o’clock position. Matters

were made worse because their African guide thought that they wanted to

cross a drift at the 12 o’clock position, and because the approach march

was conducted in the pre-dawn darkness.

Hart’s

nickname was “General No-Bobs” a direct and simple reference to the

fact that he never ducked when bullets and shells passed overhead, but also

perhaps an indirect and cleverer reference to the fact that he was certainly

not a thinking general like Lord Roberts, the other “Bobs”.

He had a

fondness for foot drill and kept his brigade in close formation. Even when

obliged to put them in extended order he sent out markers first to ensure

that the extended order was nice and neat too! Personally he was absolutely

fearless, almost to the exclusion of common sense. But his main problem as a

commander was that he expected everybody in his brigade to be absolutely

fearless almost to the exclusion of common sense too.

The

ground in the "Loop". The trees roughly mark the

river. The Boers were in the kopjes behind.

During

the approach Hart was informed three times by his cavalry scouts that there

were enemy on his left, where they shouldn’t have been, but he chose to

ignore the scouts. When he hit

the western base of the loop he realized that the map had misled him but,

since his guide insisted that the drift was straight ahead, he ordered the

Brigade forward. Dawn found them

tightly packed inside the loop. The

ground is dead flat and since the river cuts deeply into the plain its exact

position cannot be determined until you are almost right on top of the

banks. Hart, the Inniskillings

and George Barnett had the river on three sides and Boer marksmen and

artillery concealed in the kopjes beyond the river to their left and front.

The result was a massacre. A

soldier in one of the Inniskillings’ sister regiments in the brigade, the

Dublin Fusiliers, described it thus:

“For

hours, around these gallant lads, the shot like hailstones fell,

And

many a bullet found its mark in that infernal hell;

With

sad downcast face we heard the order to retire,

The

position was too strong to take beneath that falling fire . . .

Then

here’s to the gallant Dublins, and the brave old Connaughts too,

The

Border lads undaunted, and the Inniskillings true,

Side

by side, they fought and died, each man beside his “pal”,

Fighting

for

England

’s honour on the border of Natal.”

The

rest of the battle was little better from the British point of view.

The attack on the bridge was suicidal and when two batteries of

British guns advanced to support it they came into easy rifle range of the

Boers, were devastated by Mauser fire, ran out of ammunition and had 10 guns

captured. To add further insult

to the injury of the British Army that day, two companies of the 2nd Battalion of the Devons did not receive the order to retreat and were

overwhelmed, taking 102 casualties and losing 36 prisoners, including the

battalion’s colonel.

In

total 1,139 of Buller’s men were killed, wounded or captured at Colenso,

and 553 of those casualties were from Hart’s Irish Brigade.

Today the dead lie in a well-tended cemetery inside the loop.

The fatal kopjes look down in the distance, and across the billiard

table flat ground of the loop you still can’t see the river.

This is a site that should be visited by every army officer to drum

home the maxim: “Time spent in reconnaissance is seldom wasted”.

The

Irish Brigade cemetery

Uncharacteristically

Buller tried to shift the blame for the defeat.

“I was sold by a gunner”, he complained, although the gunners

certainly had no responsibility for Hart’s disaster.

Buller anguished for three days about sacking Hart but eventually

decided against this. Hart could

not understand what all the fuss was about.

He put his failure down to his soldiers going the ground but he

himself “took a cheerful view of it, ascribed it to first experiences

under fire, and said they would do much better next time”.

Botha’s view of George Barnett and his comrades was higher than

their own general’s: “I must say that I never saw anything more

magnificent than their charges at this point . . . no less than five times

they charged, and I never want to see finer bravery than I saw there” he

wrote. And, characteristically,

Botha made no attempt to take great credit for his opponent’s mistakes.

He simply wrote to President Kruger: “The Lord of our fathers has

today given us a brilliant victory”.

On

11th January 1900 Buller moved west to attempt to outflank the

Boer line. The promising chance

of a cavalry breakthrough was thrown away and by January 20th it

was decided that another infantry assault was necessary.

The attack was directed at a hill called Taba Nyama and once again

Hart’s Irish Brigade, reinforced this time by two

Lancashire

battalions, led the attack. Hart

thought that his brigade had done well because it reached the crest of the

hill, only to discover that it was a false crest and that the ridge of the

hill was still 1,000 yards away, where the Boers were waiting with a clear

field of fire. Writing after the

war, under a pseudonym because he was still a serving officer and he

didn’t pull his punches about what he saw, a Lieutenant-Colonel Grant

described Hart’s response:

“There

is nothing apologetic or doubtful about General Hart to start with, [a]

gallant fiery Irishman, too hot with the ignis sacer [holy fire] of fighting

to see anything ridiculous in a sword angrily brandished at an enemy a

thousand yards away . . . Where

will British privates not rush at the word of command?

[A]nd, in the name of pity, why are such commands given?”

Certainly the likes of George Barnett and his comrades

did not question Hart’s ridiculous gesturing.

Grant relates what happens next:

“The

artillery preparation was mere form. There

was a hasty bang, bang, bang from the artillery . . . and up from the shadows

burst the Irish and North-Countymen with a typhoon of yells and a momentum

that nothing but death could stop. But

death was there: a tremendous fire broke out from the ridge . . . The foremost

men fell in heaps, the rearmost were stopped, as all should have been

stopped, at the crestline. ‘Thus

far, and no further,’ sang the Mausers.”

Hart’s

brigade had lost 365 casualties, mostly, noted Winston Churchill, from the

Lancashire Regiments and the Dublin Fusiliers.

By this time the “Dubs” were down to 50% strength. But the

Inniskillings couldn’t have been much better off.

The battle was renewed the next day and the British made some gains,

but by the evening of the 22nd, by which time another 195

casualties had been suffered, it was clear that they could not break

through. At a council-of-war the

British commanders considered three possibilities: a night assault on the

ridge, which Churchill considered “would involve great slaughter and a

terrible risk”, an ignominious retreat, or to outflank Taba Nyama by

taking the higher hill next to it . . . Spion Kop.

On

the horizon: Taba Nyama (left), Spion Kop (centre) and Twin Peaks (right)

seen

from the British side of the Tugela

The

Battle of Spion Kop on 23rd/24th January 1900 centred

on attempts to take and hold the 1,460 metre high kop.

The Inniskillings remained on Taba Nyama, so I will not go into great

detail. But it is important to

note that this was a battle of wills. Both

sides thought they had lost. Both

sides were right. Both sides

retreated from the top of the kop. Only

Louis Botha wouldn’t give up and, throwing in his last reserve on the

morning of the 25th, the Boers found only British stretcher

bearers collecting wounded and dead on top of the hill.

The Boer will had triumphed.

Two

weeks later Buller tried, and failed, again at the Battle of Vaalkrans, just

east of Spion Kop. Again the

Inniskillings were not heavily engaged so I will not go into details but the

important thing to note is that what a fine instrument of war men like

Sergeant Barnett made for General Buller.

They took their setbacks on the chin; didn’t lose faith in their

commanders, (although Buller must have sorely tested this faith when it came

to his tactical ability, but I believe that the troops really appreciated

his genuine care for them and they repaid this) and kept going forward.

Three significant defeats in six weeks would have knocked the

stuffing out of most armies.

Whilst

George Barnett was suffering south of the Tugela what of George Hunt in

Ladysmith? The main events of

the Siege have been related in Part II, but in 2004 the Naval and Military

Press republished the “Regimental History of the 1st Battalion

Devonshire Regiment during the Boer War” by Colonel M. Jacson which

contains many little sidelights on the siege life of George and his

comrades. For instance:

9th

November 1899: First Boer attack

beaten off. “This lasted until

about 2 p.m., when the action was concluded with a royal salute from the

naval batteries and three hearty cheers which, started by the Naval Brigade,

were taken up all round the defences in Honour of the birthday of H.R.H. the

Prince of Wales. A curious

ending to a battle.” Curious

indeed. I hope that Bertie

appreciated what splendid chaps he had fighting for him.

One

of the Boer 'Long Toms' that usually made Private Hunt's life a misery,

but

occasionally fired liquorice

1st

January 1900: In addition to firing 1½ tons of real shells into the town

the Boers fired one “engraved on it 'Compliments of the Season', . . .

[containing] a busting charge of liquorice in place of melanite . . .

[a]nother

blind shell picked up was full of sweetmeats.”

Ladysmith

Town Hall. Private Hunt sat outside whilst Sgt Barnett marched past

1st

January, 1900: “Messages of good wishes to the garrison were received from

Her Majesty, from Sir Redvers Buller, and from the soldiers, sailors and

civilians of

Hong Kong

.” That was nice of us,

wasn’t it?

9th-10th

January 1900: The British

use star shell to illuminate a night attack.

The Boers had never seen them before and were: ". . . hugely elated

at the sight . . . They turned

their searchlight on to the stars . . . and cheered lustily.

They evidently considered that it was a special performance got up

for their entertainment . . .”

31st

January 1900: “horse-flesh was

issued for the first time as a ration.”

3rd

February1900: “a decoction

called 'chervil' [a pun on the popular beef essence 'Bovril'] was

issued to the men. It was

supplied by the 18th Hussars’ horses, whose bodies were boiled

down for the purpose. It was

nourishing and the men liked it, which was a good thing.

There was nothing else by which to recommend it.

The men were also allowed to go down to the chervil factory . . . and

buy the horseflesh after it had passed through the boiling process.

This did not appear appetizing, but

again the men liked it . . .” My emphasis.

Another

odd thing about the siege was that both side’s signalers chatted with each

other. A sort of fraternization

with the enemy by heliograph. When

news of the new diet got out the Boers signaled: “How do you like

horse-meat?” The British

flashed back: “Fine. When the

horses are finished we are going to eat Boer.”

Lest

all this sound too jolly, by the end of February starvation was a real

threat for the garrison and disease was knocking them down.

There were 13,500 men in Ladysmith and over 10,500 admissions to

hospital over the three months of the siege.

Despite the 'stiff upper lip' the strain was telling and 'reading between the lines' of Jacson’s account we find that even

strongly held fundamentals that had probably never even been thought about

before, were being questioned:

4th

February 1900: News received

that Buller “was to be expected shortly, and . . . that . . . Ladysmith was to

be attacked again next morning by 10,000 Boers.

Arrangements were made to meet the latter, the

arrival of the former being considered hypothetical.”

My emphasis.

13th

February 1900: “Divine Service …

The

usual 'extermination' service and prayers for the 'Right' were said,

the hymns chosen being:

There

is a blessed home

Beyond

this land of woe;

And

There

is a greenhill far away,

Sung

sadly to the accompaniment of Buller’s guns.”

The

reason why the Devons could hear Buller’s guns was because on 12th February 1900 he tried again to break through to Ladysmith.

Although George

Hunt in the garrison, and George Barnett in the relieving force had suffered

so much, so far, both still had more dark hours to go through before the

dawn.

The

Devons' memorial at Platrand, Ladysmith

back

to the contents page back

to colonial wars go

to part 4

|