|

Damn

Battleships Again

A New Approach to Pre-Dreadnought

Naval Games

by

Peter

Hunt

This

is a set of wargames rules for pre-dreadnought naval battles between 1890

and 1913 … prompted by the re-discovery of some 30 year-old 1/1200

models

When

I read the introduction to Phil Barker’s latest set of rules “Damn

Battleships Again,” (or DBSA,) my little wargamer’s heart skipped a

beat. Why?

Because just like Mr. Barker I too have some 30 years old 1/1200

models ~ which have mostly been sitting under, rather than on, my wargames

table for those years because I couldn’t find or write a decent set of

rules. It seems that Mr. Barker

and I have been seeking the same Holy Grail for the last three decades.

The Grail is of course an accurate, fun, quick and simple set of

rules ~ a very rare thing indeed, and something to treasure if you find it.

With DBSA I think Mr. Barker has done a great job so far and almost

has the chalice in his hands.

Naval

wargames have lots to commend them. They

are easy to set up, all you need is a blue cloth and the ship models and

away you go. Ship models are

available in many scales, from 1:600 to 1:6000 with prices to match.

Naval battles and the ships are well documented, so, if you like,

scratch-building your own ships is easy.

Depending on the scale you use it is perfectly possible to field

whole fleets on a 1:1 scale, something that is rarely possible for the land

wargamer. Campaigns are also

easy. So, if you are interested

in wargames, ships and the sea there are lots of opportunities.

The

“Pre-Dreadnought” period has a special charm because of the odd ball

nature of the ships concerned. In

the Ancient period there is not much difference between a Greek trireme and

a Persian trireme. The same is

true for a French or British Napoleonic First Rate, or British or German

World War One Dreadnought. This

is because in these periods the dominant technology was settled and

relatively perfected. Between

1860 and 1905 however the technological change was immense.

Warships developed from wooden vessels, relying on sails assisted by

auxiliary steam engines for propulsion and equipped with smooth bore, muzzle

loading guns, to armoured steel “dreadnoughts” with five times the

tonnage, five times the speed, and breach loading rifled guns firing shells

to 30 times the effective range as their predecessors of only 45 years

before. The

“Pre-Dreadnought” period has a special charm because of the odd ball

nature of the ships concerned. In

the Ancient period there is not much difference between a Greek trireme and

a Persian trireme. The same is

true for a French or British Napoleonic First Rate, or British or German

World War One Dreadnought. This

is because in these periods the dominant technology was settled and

relatively perfected. Between

1860 and 1905 however the technological change was immense.

Warships developed from wooden vessels, relying on sails assisted by

auxiliary steam engines for propulsion and equipped with smooth bore, muzzle

loading guns, to armoured steel “dreadnoughts” with five times the

tonnage, five times the speed, and breach loading rifled guns firing shells

to 30 times the effective range as their predecessors of only 45 years

before.

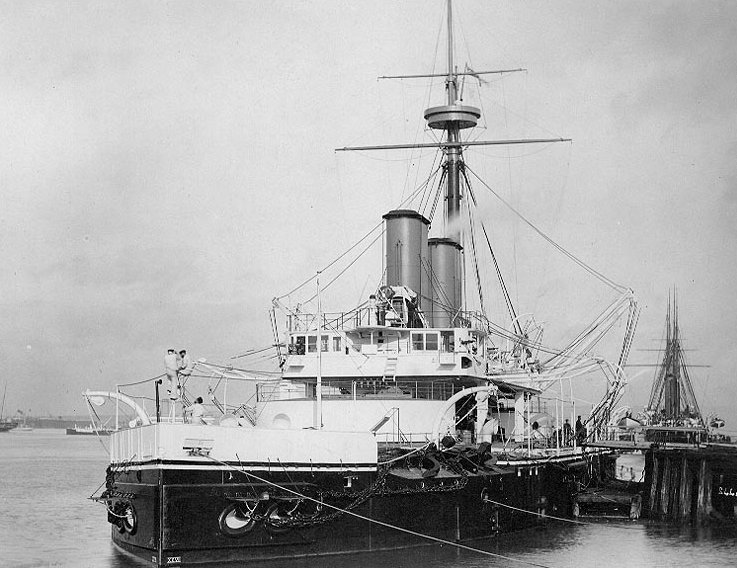

HMS

Dreadnought (battleship launched in 1875) in port

During

this period of great change ships were often obsolete soon after they were

launched, and sometimes even before they hit the water.

Applying the technology was also a conundrum.

Guns could defeat the armour of ships, so was the answer to build

ships with even more armour, or was armour pointless and should be left off

altogether? Guns were usually

inaccurate and slow firing so would other weapons like the new torpedo or

even the ship itself using its ram be decisive?

But even these imponderables were a moving target because of the pace

of technological change. The

penetration of a 12” gun increased threefold between 1870 and 1890 but

likewise the change from iron, to compound (iron and steel,) to steel and

later hardened steel armour increased the protection of ships fivefold.

Rate of fire, especially for small and medium calibre weapons,

increased dramatically in the 1890s but the range of the torpedoes carried

on the torpedo boats that many of the quick firers were directed against

increased form 400 yards to 4,000 yards in the period.

Engines gradually became more efficient but, although sails could be

dispensed with on coast defence and coast assault ships by the 1870s, a lack

of overseas coaling stations led many powers to retain sails on their

cruising ships until the end of the 1890s.

The result of all this was a “fleet of samples” as designers of

all nations tried to resolve the technological tactical and doctrinal issues

of the day. Thus, whilst in most

other periods you have “classes” of several identical ships, for the

pre-dreadnought period, especially before 1890, one or two offs were the

normal production run of ships.

Transfer

this to the realm of wargames and you have ships that are fun to build and

paint, because they are unique, and difficult to use together because of

their disparate characteristics.

And

so to the rules. What has Mr.

Barker done? As you can see here

DBSA

is still very much a work in progress but essentially he has applied the top

down “DBX” approach to naval wargames, and it works.

Command and control depends on the pip (or NIP) dice score, although

everyone gets to move no matter how bad your dice, and the movement is

simple with no rulers required. The

combat system is both quick, and to my mind, accurate, using the familiar

DBX system of a factor plus dice with different effects for a higher score

or double. Range effects and

armour penetration are covered by using different factors at different

ranges.

As

is common with most of Mr. Barker’s rules he pays a lot of attention to

time of day and weather conditions, both vital in naval games.

Interestingly he is also working on the characteristics of the crews

and commanders. Again I think

this is vital. In naval periods

where ships are very similar – such as the Ancients or Napoleonics we

mentioned above – crew quality giving differences in manoeuvrability and

fighting ability is the main factor in deciding defeat or victory, and thus

a central part of the rules. However

once you get to 1860 this disappears from practically all rules.

I think that this is because most modern naval gamers are obsessed

with accurately modelling the difference in stopping power between 11” and

12” armour, or the difference in penetration between a 45 calibre gun and

a 50 calibre gun, but forget that battles like Lissa, Manila Bay, Santiago,

Tsushima, Coronel and Sirte were decided by the quality of the crews more

than by the qualities of the ships. Mr.

Barker’s rules are still very tentative on this but I look forward to them

taking shape.

HMS

Furious (Cruiser Second Class) photographed circa 1890

Unable

to resist tinkering I humbly present some amendments to DBSA here.

An appendix, containing the statistics of current list of ships from 10 or

so navies can be found here.

I’ve been in correspondence with Mr. Barker on my ideas, some he

likes and has incorporated, most he doesn’t, but I don’t blame him.

What he is trying to do is present a generic set of rules for the

period 1890 to 1913 when the final form of pre-dreadnought ships was

becoming standardised. I don’t

have a problem with this and if I was starting to game in this period I

would buy the fleets for

Tsushima

in 1:2400 or 1:6000 scale and

use DBSA straight off. But my

fleets started off with ships from 1860 to 1900 in 1:1200 and I wanted to

use all of them, hence I use specific rather than generic values for the

ships. On the rules themselves

I’ve added to the system only in the use of torpedoes and ramming which I

think DBSA does not reflect properly yet.

Most of the rest of the nine pages consists of one-off rules that

reflect the special characteristics of special ships.

These are not vital to play but if I am going to all the trouble of

scratch building on unusual ship I want its odd characteristics to be

reflected as long as these don’t damage the flow of play.

At the risk of flattering myself the amendments can be summed up by

saying that Mr. Barker is developing a DBA for ships whilst I am (naively

probably) aiming at DBM for ships!

Finally,

as I mentioned above, one attraction of naval games is the ease of

campaigns. With no terrain to

worry about movement is simple. Campaigns

put table top games into a context that makes them more interesting than any

“equal points” game. Obviously

an umpire is the best way to sort out hidden movement but whilst I was

surfing the web in search of pre-dreadnoughts I came across the

“Aeronef” website which covers Victorian Science Fiction Airship combat

of all things! Each to his own,

though, because if they hadn’t used the names of British warships I would

never have found them and I would have missed the little gem of a playing

card based system that allows for hidden movement without an umpire.

I’ve developed it specifically for DBSA here,

but the basic concept is applicable to any wargames period, land or sea, so

even if you are not into pre-dreadnought games it might be worth a read.

Using

this system four of us fought a Mediterranean-wide campaign involving 85

ships. Over 12 hours of play,

(much of which was spent demolishing an exquisite side of beef roasted by

Jeff,) we generated and fought to conclusion a cruiser stern chase and three

fleet actions. We had a lot of

fun but the important point is no other naval set of rules I know would have

got us through four table games in 12 hours and still leave lots of time for

map moving.

The

proof of the pudding, they say, is in the eating.

My own opinion is that DBSA tastes very nice already and it can only

get better. Jeff had never even

played a post-ACW naval game before I introduced him to the first version of

DBSA but he was instantly smitten. Since

then he has built most of the Turkish, Greek and Italian navies!

How about that for a ringing endorsement?

So, if you have a fleet that has been neglected for 30 years; or

you’ve always had an interest in pre-dreadnoughts but have never done

anything about it; or you’ve never played a naval game before but are

willing to try anything once; now is your time … try DBSA.

back to other

periods

|